First of three parts

Five years after quake, emerging northern Haiti faces challenges

It’s been half a decade since a 7.0 earthquake ravaged Haiti, and a tiny northern fishing village has its first electricity, illuminating both the nation’s recovery and the obstacles slowing its progress.

Mike Siegel / The Seattle Times

A typical street scene in Cap-Haïtien illustrates the lack of infrastructure in Haiti’s second largest city, which was spared by the earthquake. Nonprofits and the U.S. government have been trying to make this region’s economy self-sustaining, with mixed results.

Mike Siegel / The Seattle Times

Click to enlarge | Schoolgirls walk home to the gated community that locals call Djon Djon Ville, where signs of Haiti’s renewal are evident.

By Ángel González

Seattle Times business reporter

MADRAS, Haiti — The village of Madras lies at the end of a dusty road in a forgotten corner of Haiti’s northeastern plains, not far from where Christopher Columbus is thought to have established the first European settlement in the “New World” in 1492.

Most of its inhabitants have long lived in a way Columbus would have found familiar: gathering salt and small fish to dry in the sun, and relying on oil lamps for light.

Last summer the town got its first electricity, thanks to an $18 million, U.S.-financed power plant built to feed the nearby Caracol Industrial Park — an ambitious and still-unfulfilled effort to turn Haiti’s impoverished north into a hub of industry.

Now Madras is one of the few places in Haiti with reliable, 24-7 power. Not even the impoverished nation’s sprawling capital, Port-au-Prince, has that luxury. Fourteen households in this town of about 85 families have signed up for it.

“Before electricity, we needed to go to bed early,” said Abraham Jaclaire, a gaunt but neatly dressed fisherman, as a French rap song thumped on big loudspeakers nearby.

“Now we have music, entertainment, cold drinks. We go to sleep at midnight.”

The power plant and industrial park are examples of the international community’s drive to not just repair but reinvent Haiti’s economy after the Jan. 12, 2010, earthquake that killed more than 200,000 people and devastated what was already the poorest country in the Americas. They illustrate how that effort has resulted in much progress — but also how much more needs to be done.

In the aftermath of the 7.0 quake, donors pledged $16 billion in funding through 2020. The $9.5 billion disbursed in the first two years was three times the Haitian government’s revenue in that same period, but some critics say that only a fraction ended up in Haitian hands.

While the flood of money was key in helping Haiti overcome the worst disaster in its history, the country remains more fragile than any other in the hemisphere.

Mike Siegel / The Seattle Times

The Mapou River runs through densely populated Cap-Haïtien into the Atlantic Ocean. Cap-Haïtien is Haiti’s largest city in the north, where the international community is trying to not just repair but reinvent Haiti’s economy after the Jan. 12, 2010, earthquake that killed more than 200,000 people and devastated the poorest country in the Americas.

Much aid was geared to immediate relief around the hard-hit, dysfunctional capital of Port-au-Prince, which accounts for 60 percent of the nation’s economy. But hundreds of millions of U.S. dollars have been spent here in Haiti’s northeast, an area untouched by the quake, in hopes of creating new, self-sustaining industries.

The progress — and ultimately, Haiti’s ability to stand on its own — will be put to test this year.

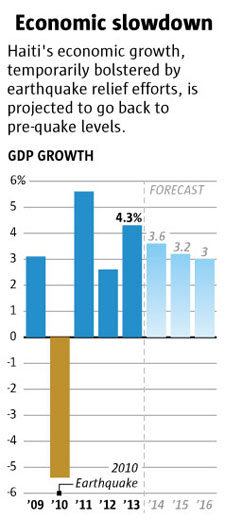

The flood of relief aid, which resulted in a brief economic boom, has long been receding. High-profile initiatives such as the Clinton Bush Haiti Fund disbursed their funds in the first two years and have stepped back.

But now, five years after the quake, a critical test is coming: help from petroleum-rich Venezuela — Haiti’s main donor aside from the U.S. — hangs by a thread as low oil prices pressure the South American country.

There’s also a brewing political crisis due to long-delayed parliamentary elections, which could mean a majority of Haiti’s legislators will leave office on Jan. 12 with no replacement. A tentative agreement has been struck to extend their terms, but it’s not a done deal.

Some see the dwindling assistance as a critical spur for Haiti, which has leaned on foreign help for decades. “Aid after the earthquake was needed,” said Philippe Girard, an academic who specializes in Haitian history at McNeese State University in Louisiana. “Five years beyond that, there’s the point where you need to transition to something else.”

Mike Siegel / The Seattle Times

Cap-Haïtien, Haiti’s second-largest city with a population of 190,000, is located on the north coast of Haiti and has become a center of efforts to reinvent Haiti’s shaky economy.

Changing a mindset

Nowhere is the effort to overhaul Haiti’s economy more evident than in the country’s northern plains — the historical cradle of Haiti and now perhaps the key to its future.

Unlike the moonscape-like roadways common all over Haiti, Cap-Haïtien boasts decent roads connecting it with the Caracol industrial park and the border with the Dominican Republic. Still, the ride is punctuated by steep speed bumps known here as “donkey backs.”

There’s also a university, named after Haitian independence hero Henri Christophe, built by the Dominican Republic for $30 million.

And in October, American Airlines launched the first daily flight connecting Miami with Cap-Haïtien’s airport, named after late Venezuelan firebrand Hugo Chávez.

But the challenges, cultural and structural, are in plain sight too.

Take the electric plant, built by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and run by NRECA, a U.S. organization for electric co-ops. The power isn’t too expensive: The average bill in Madras is about $10 a month, more or less what many pay for their cellphones.

But users of the rickety state-owned power grid also were accustomed to not paying the bills, or to stealing power outright.

“To get this mindset to turn around is not easy,” says Myk Manon, NRECA’s country director for Haiti.

He says that the new university, now in the hands of the Haitian government, hasn’t paid its bills and has no power.

Cradle of Haiti

Nestled between the imposing mountains of the Massif du Nord and the Atlantic Ocean, Haiti’s verdant northern plains were once the heart and the economic engine of this island.

In the 18th century, hundreds of thousands of slaves worked the French colony’s sugar and indigo plantations; the city now called Cap-Haïtien was known as the Paris of the Caribbean. While Americans were fighting for their freedom from Great Britain, this colony was the world’s wealthiest.

In the tumultuous years that followed the French Revolution, the Haitian slaves rose against the white ruling class, killing most of those who didn’t flee.

Out of the rubble rose the Western Hemisphere’s second independent state, one that made slave owners from Louisiana to Brazil tremble. In the 19th century Haiti was rich and powerful enough to annex its Spanish-speaking neighbor, now known as the Dominican Republic.

Symbols of that strength are still visible in the ruins of the baroque palace and the huge fortress built by Christophe, a leader of the anti-French revolt who later was crowned king of the northern part of the country.

The king’s emblem was a phoenix, and his motto was “I am reborn from my ashes” — as relevant now as it was then.

Mike Siegel / The Seattle Times

The Sans-Souci Palace was the royal residence of King Henri Christophe of Haiti. It is located in the town of Milot, in the northern part of Haiti. Students from a local school use the crumbling palace as a quiet place to study.

But nowadays Haiti is poor. Its population of 10 million is about the same as that of the Dominican Republic, whose economy is seven times larger. Haitians’ life expectancy of 63 is 10 years less than that of their Dominican neighbors.

More than 75 percent of the population lives on less than $2 a day, and about two-thirds are unemployed, according to U.S. government figures.

More than 40 percent of Haitians live in the Port-au-Prince metropolitan area, where most of the infrastructure and jobs are as well. Sitting on a hot coastal plain surrounded by steep, deforested mountains, the city is jampacked with people selling charcoal and water. Much of the debris from the earthquake has been cleared out, but plenty of scars remain — crumbled houses, a cathedral in ruins.

The north is also poor, and though it was spared by the quake, it’s often pummeled by floods. From here sailed many of the Haitian boat people who in the 1990s sought to reach the U.S. — often ending up returned to Haiti or in a watery grave.

In Cap-Haïtien, the country’s second largest city, merchants peddle salvaged wire, used bicycle tires or clothing bought in the Dominican Republic amid heaps of trash and ditches flooded by rainfall.

Mike Siegel / The Seattle Times

Click to enlarge | In late October, dozens of locals dug through debris after hundreds of shacks had been razed along the waterfront to make room for a grand boulevard in Cap-Haïtien. People sought metal scraps or big pieces of rubble that they piled up and sold to passing trucks.

Garland Potts / The Seattle Times

Source: World Bank Data

The centerpiece of the hoped-for rebirth of the northern plains is the Caracol Industrial Park. Located 30 minutes from Cap-Haïtien and 45 minutes from the Dominican border, it benefits from favorable trade treatment in the U.S. for Haitian textiles. The park’s anchor tenant is the South Korean company SAE-A, one of the world’s largest textile manufacturers, which makes T-shirts there.

The $300 million, 590-acre park, opened with great fanfare in 2012 by then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and former President Clinton, also showcases the limitations of projects to redraw Haiti’s economic map.

Caracol is an island of order with wide streets and modern industrial buildings. Elsewhere, Haitians mostly travel tightly packed inside or atop brightly painted “tap-tap” trucks that stop anywhere; Caracol has a fleet of about 40 well-maintained buses to carry workers home to nearby towns.

When the Clintons and Haitian head of state Michel Martelly inaugurated Caracol, State Department officials calculated the park would create up to 65,000 jobs, a third of them by 2016. It was an ambitious target considering that at its peak in the 1980s, before it was gutted by a U.S. embargo in the 1990s, the Haitian textile sector employed 100,000.

This player was created in September 2012 to update the design of the embed player with chromeless buttons. It is used in all embedded video on The Seattle Times as well as outside sites.

Mike Siegel / The Seattle Times

Driving down the street in Cap-Haïtien.

Mike Siegel / The Seattle Times

Click to enlarge | Tap-tap vehicles serve as public transportation in Haiti. To use them, you pay the driver a small fee to get on, then “tap tap” the side of the vehicle to alert the driver when you want to get off.

“We have been united behind a single goal — making investments in this country’s people and your infrastructure that help put Haiti finally on the path to broad-based economic growth with a more vibrant private sector and less dependence on foreign assistance,” Secretary Clinton said at the 2012 event. “And we believe that our work here in Haiti and here in the north is beginning to show results.”

So far, however, the park employs only 4,766. That’s partly due to delays in construction of new warehouses because of tightened building standards, says Liszt Quitel, chief of staff for the CEO of the Haitian government agency that runs industrial parks.

It’s also hard to ship goods out since Caracol lacks a big local port. The U.S. Government Accountability Office says U.S. officials overestimated how quickly one could be built in the area. After fruitlessly trying to lure investors for a new port in nearby Fort Liberté last year, the U.S. government decided to expand the port of Cap-Haïtien.

Mike Siegel / The Seattle Times

Click to enlarge | More than 4,000 Haitians employed at the Caracol Industrial Park in northern Haiti work for South Korean company SAE-A, one of the world’s largest textile manufacturers, which makes T-shirts there.

Mike Siegel / The Seattle Times

Click to enlarge | In the town of Caracol, a woman carries her laundry along a dirt road. Caracol is located between the Dominican Republic and Cap-Haïtien in northern Haiti, where some hope an industrial park near the border can bring jobs and modern amenities to a country where both have always been scarce.

Ana María Sáiz, an official for the Inter-American Development Bank (IADB), one of Caracol’s backers, said the bank now predicts the project will hit the 20,000 job mark by 2020. “The initial economic evaluations were much more optimistic,” she acknowledges.

Nevertheless, the initially glacial pace of job growth accelerated last year. The payroll at Caracol doubled in 2014 and a senior U.S. State Department official said that by the end of 2015 the park could double again, to 9,000 workers.

“There’s more demand for space in the park than we have space,” said the official, who can’t be named under State Department rules.

Some of the park’s features are truly avant-garde. For instance, its water treatment plant uses ponds of vegetation to process human waste.

But the plant also has suffered from the sort of difficulties that permeate Haiti’s economic environment: Completion has been delayed because construction material was stuck for months at customs. That was crucial because “Everything you see here is imported,” said Luis Jaime de la Cueva, who oversees a Spanish consortium’s work on the facility.

De la Cueva also said the plant, which is already operating, has had to deal with an unforeseen decision by SAE-A to funnel polluted laundry water through the facility although it was only designed for residential waste.

Caracol has huge, cavernous cafeterias with tables and benches where workers can go at lunch hour. But they are mostly unused, as many workers prefer to sit outside, on the ground, just as they do in their villages. The pay of about $5 a day is the minimum wage, but some complained it’s too little to afford basic necessities. Some also chafe at the factory discipline.

“It’s tiresome work,” said Ronise Erilus, a 30-year-old textile worker who says she has to finish 100 shirts per hour.

“If we are absent for one day we get penalized for two,” missing out on $10 in wages, said Johanne Pierre, who does quality control. Sitting outside during her lunch hour, Pierre also complained about the 6-day workweek, which means “We don’t have time to do our own things” in a place where chores such as shopping and laundry are time-consuming.

Quitel, the official at the government agency in charge of industrial parks, said low pay and long hours are inevitable at the current stage of Haiti’s development. “It’s an obligatory passage,” he said during a tour of the site.

He said many of these workers, until recently fishermen and street merchants, are inexperienced, and it will take a while for them to become an effective — and better paid — workforce.

Quitel said the Korean manufacturer’s company policy prohibited access to the plant, though he said they were “very comfortable” compared to other industrial facilities around the country.

Mike Siegel / The Seattle Times

The Dominican Republic and Haiti are separated by the Massacre River, the scene of many battles. Now there is an industrial park nearby, and a busy cross-border market.

Credits

Reporter: Ángel González

Photographer / videographer: Mike Siegel

Project editor: Rami Grunbaum

Producer / Web designer: Gina Cole

Print designer: Bob Warcup

Copy editor: Karl Neice

Graphic artists: Mark Nowlin, Garland Potts

Photo editor: Fred Nelson

Video editor: Lauren Frohne

The U.S. development effort also stumbled in other areas: a development of 750 small, new homes ran into cost overruns and delays due to design changes, labor disputes and protests, according to a report by USAID’s Inspector General.

But the brightly colored village and its glittering, Korean-funded school are now complete. Locals call it “Djon Djon Ville,” after a local mushroom that resembles the black water towers on the roofs.

The massive development effort has generated some ripple effects. A big banana plantation next to Djon Djon Ville stands out as a symbol of renewed vitality. More than 7,000 households in the region now have the country’s most reliable electricity. The IADB’s Sáiz says that more than 120 businesses have been born as a result of the improvements.

One such business is Joseph Faude’s water purification shop in Caracol.

The energetic 44-year-old businessman hooked up a reverse osmosis machine to purify water from a well in his backyard. Now Faude and his six employees package the water in small plastic bags, which merchants sell on the streets.

“Water is life,” he said.

Girard, the McNeese professor, says that despite the challenges, it’s projects like Caracol, as well as tourism, that hold the key to Haiti’s future once basic infrastructure issues are solved.

“You have a big untapped potential,” he said. Given the country’s abundance of unemployed people and its proximity to the U.S., “There’s no reason the U.S. should import things from Vietnam or China.”

Ángel González: 206-464-2250 or agonzalez@seattletimes.com. On Twitter: @gonzalezseattle.