Originally published April 3, 2012 at 9:31 PM | Page modified April 4, 2012 at 1:24 PM

Amazon warehouse jobs push workers to physical limit

Amazon.com strives to be increasingly efficient to ship customers' orders as quickly as possible from its fulfillment centers around the world. And while the company has a safety record better than most, some warehouse employees say the relentless drive to boost production wears them down and costs them their jobs.

Seattle Times staff reporters

DAVE CRUZ / SPECIAL TO THE SEATTLE TIMES

Amazon.com's motto is displayed in its state-of-the-art West Phoenix fulfillment center. Although this 2-year-old center has air conditioning, some older Amazon warehouses did not, and workers suffered from heat-related illnesses trying to keep up with the relentless drive to boost production.

HAL BERNTON / THE SEATTLE TIMES

Connie Milby worked at Amazon's fulfillment center in Campbellsville, Ky., for 10 years. As a "picker," she could walk more than 10 miles a day to retrieve items ordered by Amazon customers.

HAL BERNTON / THE SEATTLE TIMES

Workers arrive for a shift at one of Amazon.com's oldest fulfillment centers, in Campbellsville, Ky. Early on, founder Jeff Bezos impressed workers with his visits, but one former safety manager said the center later became "a brutal place to work."

DAVE CRUZ / SPECIAL TO THE SEATTLE TIMES

Amazon has four fulfillment centers in the Phoenix metro area, with a combined total of more than 4 million square feet. As part of a strategy to reduce customers' waiting time after making a purchase, Amazon has set up dozens of distribution warehouses around the world. The workers at this center shipped a record 2,086,548 items in one week.

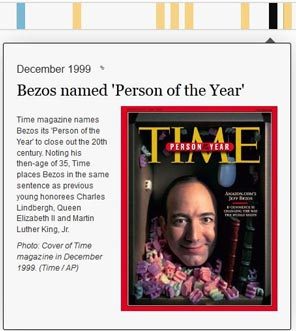

Timeline: How the fortunes of Amazon and Jeff Bezos have grown

Click on the image above to explore a timeline about Amazon and its founder, Jeff Bezos.

Part 1: Behind the smile in Seattle

Part 2: A hammer on the publishers

Part 3: Pushing back on sales taxes

Part 4: Worked over in the warehouse

From the editor

![]()

CAMPBELLSVILLE, Kentucky —

On an average day, 51-year-old Connie Milby covered more than 10 miles in her tennis shoes, walking and climbing up and down three flights of stairs to retrieve tools, toys and a vast array of other merchandise for Amazon.com shoppers.

She filled online orders for more than a decade, working through summer heat and winter chill inside the company's south-central Kentucky warehouse.

One constant was the pace that Milby tried to keep to avoid write-ups from her supervisors that could put her $12.50-per-hour job at risk.

"At my age around here, there are not very many other opportunities to make what we make," Milby said before beginning her 6:30 a.m. shift last October. "As long as my body holds up, I will keep working. But the way it feels, I don't know how long that will be."

Milby's job here in Kentucky is a world away from Amazon's rapidly expanding campus in Seattle's South Lake Union neighborhood, where high-tech talent has created one of the cutting-edge companies of the Internet age.

She has been part of the massive blue-collar work force required to fulfill founder Jeff Bezos' ambitious vision of Amazon as a company that rivals Microsoft and Apple in technological prowess, but also offers one-stop shopping worthy of a Wal-Mart.

According to Amazon, more than 15,000 of the company's full-time employees work in its U.S. warehouses, called "fulfillment centers." Amazon is expanding its work force at a breakneck pace to staff its global network of some 70 centers — 17 opened just last year.

In an industry that often offers scant benefits, Amazon provides full-time employees with stock shares after two years on the job, a matching 401(k) and health insurance. Temporary workers, such as those hired during the holiday rush, can buy medical coverage through staffing agencies.

Just as Amazon tracks and analyzes the habits of online shoppers, the company has created a hyper-efficient warehouse culture where worker performance is continually monitored and measured in pursuit of slashing costs and shipping times.

By the numbers, Amazon's safety record stacks up well in an industry that has long been criticized for harsh working conditions and injuries.

"We measure progress on safety using the 'recordable incidence rate,' which is the primary metric defined by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration [OSHA]," Amazon said in a written statement last week. "From Jan. 1, 2006, to Sept. 30, 2011, our U.S. fulfillment network had an annual average recordable incidence rate ranging from 2.5 to 4.2. These rates are lower than for auto manufacturing, the warehousing industry and even for department stores.

"To put it simply, it's safer to work in an Amazon fulfillment center than in a department store."

But a federal lawsuit filed in Pennsylvania and interviews with a physician and warehouse workers in Washington and Kentucky suggest that the numbers Amazon is reporting may not tell the whole story.

In the lawsuit, settled in July, Amazon warehouse worker Paul Grady said a warehouse safety worker in Allentown, Pa., instructed him to tell emergency workers that his hip injury was not work-related, even though he says it was. Grady's injury was first reported in an investigation of Amazon's Pennsylvania warehouse operations last year by the Allentown (Pa.) Morning Call, which also found indoor temperatures soared so high that Amazon had ambulances parked outside to take workers to the hospital.

Three former workers at Amazon's warehouse in Campbellsville told The Seattle Times there was pressure to manage injuries so they would not have to be reported to OSHA, such as attributing workplace injuries to pre-existing conditions or treating wounds in a way that did not trigger federal reports.

Pam Wethington, a former Campbellsville employee, took several months off work in 2002 because of stress fractures in both feet. She says her doctor attributed the injury to walking miles on the concrete floors of the warehouse, but Amazon disputed that the fractures were work-related.

A former warehouse safety official said in-house medical staff were asked to treat wounds, when possible, with bandages rather than refer workers to a doctor for stitches that could trigger federal reports. And warehouse officials tried to advise doctors on how to treat injured workers.

"We had doctors who refused to work with us because they would have managers call and argue with them," he said.

Dr. Jerome Dixon, a Campbellsville physician who treated injured and sick workers referred by Amazon, said the company never tried to dictate what care a patient should receive. But he did recall questions from managers about why he opted to give an injection that would turn an injury into a federal "recordable incident" rather than provide some other treatment.

"If you give a shot of an anti-inflammatory, it makes the patient get better faster," Dixon said. "Sometimes I did give that shot, and maybe they didn't like that. I would say, 'Sorry, I know it's a recordable and makes you do paperwork.' "

Amazon declined to address the specific complaints about its handling of recordable injuries.

"Since we ship hundreds of millions of packages a year, employ tens of thousands of associates, and record millions of work hours, it isn't possible to accurately portray the effectiveness of our procedures with anecdotes," the company said in a statement last week. "To accurately reflect our operations, any reporting must focus on examining our safety record as measured against relevant industry benchmarks."

The company did note, however, that it has "processes to help ensure the proper reporting of recordable injuries," including independent audits, an anonymous hotline for employees to report workplace concerns and a policy that lets employees choose their own doctors.

Unrelenting efficiency

To get a better — although not comprehensive — sense of life on an Amazon warehouse floor, The Seattle Times interviewed more than 40 current and former Amazon warehouse workers. Reporters visited Campbellsville, home of one of Amazon's oldest fulfillment centers, and Sumner, Pierce County, home of one of its newest facilities. A reporter also toured a two-year-old warehouse in West Phoenix while accompanied by company officials.

They found some employees who relished the challenges of working at an innovative company and appreciated the emphasis on safety. But they also found others who said that in its relentless push for efficiency, Amazon was quick to shed workers who, regardless of their tenure, could no longer measure up.

The majority of the current and former workers would speak only if guaranteed anonymity because they were worried that speaking publicly could harm their careers.

Of the three sites, Times reporters heard the harshest complaints about Campbellsville.

Amazon was greeted as an economic savior when it opened its warehouse there in 1999, soon after the town's largest employer, Fruit of the Loom, shut down its textile plant.

The county's unemployment rate then topped 22 percent. The state offered $19 million in tax credits to help offset the company's $38 million investment. And Campbellsville, located within a day's drive of more than half the nation's population, had geography in its favor.

The area boasted a work force that, while somewhat older in profile than elsewhere in the Amazon network, had long tackled tough blue-collar jobs. Amazon hired more than 700 full-time workers and suddenly became the largest private employer in Taylor County, according to county statistics.

Early on, Bezos impressed the employees by taking time to work with warehouse crews during visits to the town.

"The Amazon motto is 'Work hard, have fun and make history,' and that's what we did," said Wethington, who worked for more than a decade at the Campbellsville fulfillment center before she was fired last year for a safety violation.

But over time, said former workers at Campbellsville, production pressure from headquarters intensified amid constant turnover.

As those tensions spilled onto the warehouse floor, Amazon gained a reputation as a difficult place to earn a living.

"There would be phone conferences [with Seattle], and all this screaming, about production numbers. That was always the problem; the production numbers weren't high enough," said a former safety manager with oversight of the warehouse who spoke on condition of anonymity. "This was just a brutal place to work."

Former managers said the company created a work environment where employees who complained about conditions, including excessive heat, risked retaliation.

After nearly two years on the job, one former manager was troubled enough about conditions to write an email to an Amazon regional vice president. He says he detailed concerns about unreasonable expectations of workers during extremely hot days, how production rates were set and other issues.

A week later, the former manager says, he was accused of a minor rules infraction and given the choice of leaving the company or getting fired.

"I said that this makes no sense," he recalled. "There were huge problems at Campbellsville, and I wanted them to do an investigation." The tough tactics extended to the treatment of sick and injured workers, according to a former human-resources employee.

"They would have meetings on how we could get rid of people who were hurt. It was horrible," she said. "I would try to find them [the workers] light-duty jobs that they could do, and they [managers] would say no. They wanted the workers to exhaust their time off so they could fire them."

Jennifer Owens, who had worked at Campbellsville for more than a decade, said she lost her job last September after she returned to work from an approved medical leave for neck pain caused by an auto accident.

"They just came back and said, 'You're fired,' " Owens recalled. "I really didn't say anything. It was like — God, I can't lose my job. I got to have my health insurance."

In Campbellsville, as in Pennsylvania, Amazon employees struggled with heat. Each summer, former employees said, some workers were taken to the hospital because of heat illness.

Although they got longer breaks, workers said, production goals did not ease as temperatures climbed.

A former Amazon safety official in Campbellsville wanted to discuss reducing the work pace when temperatures pushed over 100 degrees but says he never dared broach the subject with management. "I knew that was off the table — not an option," said the former safety official. Instead, he outfitted roving managers with backpacks full of Gatorade, which they served to workers so the workers wouldn't have to leave their posts.

The summer heat also drew the attention of Dixon, the Campbellsville physician.

"It was definitely an issue," said Dixon, who confirmed that some workers were sent to the emergency room. "I told my patients they need to drink more water, and had a conversation with management to figure out what we could do."

Susan Draper, director for Kentucky's Division of Occupational Health and Safety Compliance, noted that Amazon was not the only warehouse operation that had trouble with excessive heat. She said Amazon has responded well to concerns raised by state inspectors and was "always cooperative."

Amazon installed air conditioning last summer at its warehouse in Lexington, which had been the subject of two heat complaints to the state, and plans to air-condition the rest of its Kentucky warehouses, including Campbellsville, this year.

It's all about the customer

At Amazon warehouses around the country, work shifts often begin with stretches and pep talks focused on customer service, which Amazon founder Jeff Bezos has repeatedly said is key to the company's survival.

"The first thing I know is that you need to obsess over the customers," Bezos declared in a 2009 video. "I can tell you that we have been doing this from the very beginning, and it is the only reason that Amazon exists today in any form. We always put the customer first."

The drive to serve customers has put Amazon on the leading edge of innovation in the warehouse industry, which increasingly has been restructured to serve online retailing.

Amazon has abandoned the old model of parking merchandise in a few centralized locations to open warehouses across the country and around the world.

These distribution hubs store and ship millions of items offered by Amazon, and, in a burgeoning new business, also store and ship the products of other merchants who sell on Amazon.com.

This "soup to nuts approach" gives Amazon a leg up on competitors who can't offer the same mix of services, said Steve Banker, a logistics industry analyst with Massachusetts ARC Advisory Group.

In Washington state, the distribution network includes the 500,000-square-foot warehouse opened last year in Sumner and a prototype Bellevue facility, operated by a subsidiary, Amazon Fresh, that delivers a wide range of groceries.

At these centers, high-tech systems help to choreograph — and minimize — the workers' movements and track their productivity in precise detail.

As pickers take an item from a shelf and scan it with a handheld device, a computer assigns them the next item to grab based on their location. The goal is to get pickers to take as few steps as possible.

At the 2-year-old, air-conditioned warehouse in West Phoenix, workers, most of whom appeared young and fit, moved a record 2,086,548 items from the shelves to the loading docks in one week, an accomplishment emblazoned on a banner in the middle of the warehouse. The 1.2 million-square-foot building hums — literally, and at times loudly — as conveyors whisk items across, around and through the building at speeds of about 20 mph.

"I'm obsessed with efficiency, and this is the most productive place I've ever seen," said Shelby Lewis, a 22-year-old West Phoenix warehouse worker who wants to make her career at Amazon. "We change stuff quickly here. It's constantly getting better."

Just like at West Phoenix, performance measurement is paramount at Amazon's Sumner warehouse.

Employees are coached by a "problem solver" who roams the warehouse floor with a laptop on wheels and offers feedback on how to do things better. Each morning and afternoon, during breaks, management calls out the names of workers who have made their goals.

"They are a driven corporation — more driven than any place I've worked," said one worker who handles freight.

But those who don't measure up, that worker and others said, can quickly get the boot.

A supervisor in Sumner, speaking on condition of anonymity, said the company keeps track of mistakes, and penalizes workers for errors such as not properly scanning merchandise, even if the scanner itself caused the problem. Safety violations and other missteps also can result in write-ups that lead to firing, employees said.

The company declined to discuss decisions involving specific employees but said in a written statement that, "like most companies, we have performance expectations for every Amazon employee — managers, software developers, buyers and fulfillment center employees — and we measure actual performance against those expectations."

Keeping unions out

Amazon has built its network of fulfillment centers in an era when union membership has been declining. Organized labor now represents less than 8 percent of the warehouse workforce.

In Campbellsville, the mean wage for full-time workers — including incentive pay and stock options that vest after two years on the job — tops $14 an hour, according to an Amazon official. That is substantially higher than the mean hourly wage of less than $10 an hour for warehouse workers in south-central Kentucky. But it lags far behind the top tier of unionized workers in the area, who may make more than $20 per hour after four years on the job at a Kroger grocery warehouse, according to Kenny Lauersdorf with Teamsters Local 89.

Early on, Amazon took a hard line against unions. A high-profile organizing effort by the Communications Workers of America at an Amazon call center in Seattle ended in 2001, when the center was shut down and some 400 workers were laid off as part of a larger company restructuring. At the time, Bezos said union issues played no role in the decision.

Former employees at Amazon distribution centers say that workers are warned of the perils of unions. "We had a meeting once a year, and they would put the unions down and say that they would take money out of our checks," said Owens, who worked at the Campbellsville plant.

Much of labor's attention in recent years has been focused in Southern California, where some of the most notorious worker abuses have occurred in a concentration of warehouses that supply Wal-Mart and other big-box retailers. (Amazon has no warehouses there.) Union organizers said the Southern California warehouse industry relies heavily on temporary workers, most of whom get no health insurance. Two companies there were hit with more than $1 million in state fines for failure to keep proper pay records, and they face a class-action lawsuit alleging violations of minimum-wage laws.

In January, the state hit two other warehouse companies with more than $256,000 in fines for safety violations.

In contrast, Amazon has been fined less than $6,500 for safety violations at its facilities around the country during the past 10 years of operations, according to a review of federal records.

Dave Clark, Amazon's vice president for global customer fulfillment, says the company offers its workers financial incentives tied to safety. Those payments can be affected by the number of injuries at the facility, and also by individual tasks — such as whether an employee follows the rules for using and properly storing equipment, employees said.

"If your injury scores are low, you get more money," said a receiving clerk at the Sumner warehouse who earned $12.50 an hour, plus an extra $200 one month because of the warehouse's safety record.

Investing in robots

No one expects Amazon's fast-growing need for warehouse labor to slow anytime soon.

The company is rapidly adding warehouses around the globe as international sales grow.

And if Amazon's experiment with selling groceries proves successful in Bellevue, that could spur another major round of expansions near major urban centers.

But Amazon appears to be looking at ways of turning more of the blue-collar work over to robots. In early March, Amazon paid $775 million to purchase Kiva Systems, a company that has developed robots that can retrieve items stowed in the warehouse and bring them to warehouse employees.

"Amazon has long used automation in its fulfillment centers, and Kiva's technology is another way to improve productivity," said Clark, the Amazon vice president.

Zappos, a subsidiary of Amazon, already has tried out robots developed by Kiva in a warehouse in Shepherdsville, Ky. A Kiva robot can pick 200 to 400 items per hour, substantially reducing labor requirements, according to Kiva officials.

But so far, Kiva robots have operated only on a single floor to retrieve merchandise. Amazon's warehouses store items on multiple tiers, and allowing the robots to reach all that merchandise would require major infrastructure investments, according to Dave Tavel, executive vice president of AHS, a company that helps automate warehouses.

Tavel doesn't expect any quick replacement of Amazon's human pickers with robots.

"Labor," Tavel said, "is a lot more flexible."

With people, companies can quickly expand their work forces during seasonal surges, trim as the orders ebb, and shed workers who fail to meet production standards.

At Campbellsville, Amazon employees see that played out regularly.

Milby said her 10 years there left her with a bad foot from too many hours on the concrete floors.

Two weeks ago, she was fired.

"I was terminated for low productivity," Milby said.

Hal Bernton: 206-464-2581 or hbernton@seattletimes.com. Susan Kelleher: 206-464-2508 or skelleher@seattletimes.com.

Seattle Times reporters Amy Martinez and Justin Mayo and staff researchers Miyoko Wolf and David Turim contributed.