Originally published June 26, 2005 at 12:00 AM | Page modified March 16, 2010 at 4:53 PM

New blood-pressure guidelines pay off — for drug companies

Blood-pressure readings once considered safe are now considered cause for alarm because of guidelines bearing the marks of the pharmaceutical industry.

Seattle Times staff reporter

ALAN BERNER / THE SEATTLE TIMES

Seattle City Councilwoman Jean Godden had a serious allergic reaction to a hypertension drug. "The whole side of my face was swollen and my tongue looked like a baseball," she recalls.

STEVE RINGMAN / THE SEATTLE TIMES

At the American Society of Hypertension (ASH) convention in San Francisco last month, doctors check the Bristol-Myers Squibb counter in a room full of drug-company literature and salespeople. Critics say drug companies, which pay one-third of ASH's $4.4 million budget, exert undue influence on the group.

STEVE RINGMAN / THE SEATTLE TIMES

Dr. Curt Furberg of Wake Forest University wants doctors around the world to use diuretics as the first course of treatment for hypertension. Diuretics are less expensive and safer than newer drugs.

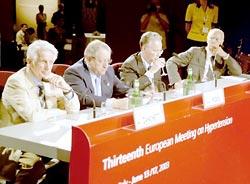

DUFF WILSON / SPECIAL TO THE SEATTLE TIMES

Two Italian doctors, Alberto Zanchetti, left, and Giuseppe Mancia, second from right, sipping water, led efforts to update global hypertension guidelines. Both have ties to drug companies.

HARLEY SOLTES / THE SEATTLE TIMES

Dr. Bruce Psaty, a University of Washington professor and nationally recognized drug-safety expert, has earned the enmity of drug makers through his research on blood-pressure drugs.

HARLEY SOLTES / THE SEATTLE TIMES

Outside the World Health Organization headquarters in Geneva, a statue of a child leading a blind man commemorates the agency's work to wipe out river blindness, a disease that is endemic in parts of Central Africa. The statue was donated by the drug company Merck.

HARLEY SOLTES / THE SEATTLE TIMES

Treatment guidelines endorsed by the World Health Organization have worldwide impact. Here, Aldo Argola, a WHO librarian in Geneva, loads treatment guidelines and medical books into a trunk that will be sent to a health center that lacks up-to-date information. The WHO has sent these portable medical libraries to more than 1,400 health centers in 60 nations.

Jean Godden felt as fit as a 71-year-old could hope for. Then a medical panel published new guidelines for treating high blood pressure, and her doctor tried her on three different pills.

One of them almost killed her.

Godden, a Seattle City Council member and former Seattle Times columnist, had lived with moderately high blood pressure since her 40s and took a daily diuretic to head off potential problems.

Diuretics, or "water pills," stimulate the kidneys to remove excess water from the blood, reducing pressure on the heart. They have been a proven hypertension treatment for a half century, with minimal side effects other than more frequent urination.

Godden's father had died of heart trouble at 49, so she was glad to take the white generic pill that cost pennies a day.

"Naturally, I want my life to be saved from a stroke or heart attack," she said.

By avoiding salt and caffeine, exercising and taking diuretics, Godden held her systolic blood pressure — the first number in the two-number reading — to between 140 and 150.

For years, doctors considered 120/80 to be ideal and anything under 140 to be OK. But a change took place in May 2003, when American doctors got new advice from a government-sanctioned medical panel called the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure.

Systolic pressure as low as 120 could be unsafe, the panel said. It also established a new condition, called "prehypertension," systolic pressure from 120 to 139, and said millions more people should take hypertension drugs to save their lives.

"It used to be your age plus 100 was perfectly OK," Godden said. "Somehow, now, if you're a 140, this is high blood pressure."

After learning about the lower targets, Godden's internist, Dr. Robert Saunders of Seattle, called her. "I said, 'Look, we've got to do something different here. I can't live with this. It's not good for you,' " Saunders recalls.

He told her she needed to get down to 120 over 80 and insisted she add another medicine.

Saunders prescribed a low dose of lisinopril, a newer drug known as an ACE inhibitor, which works on hormones to relax arteries. But after five months, Godden's blood pressure didn't drop low enough, and Saunders was concerned. He doubled the dose.

That first night Godden woke up in a panic. "The whole side of my face was swollen, and my tongue looked like a baseball," she said.

She considered calling 911 but instead drove herself to the University of Washington Medical Center and was checked into the emergency room, where she was given Benadryl to counteract the swelling. Doctors there told her she had suffered an allergic reaction that could have killed her.

The next day, she called Saunders, and he prescribed clonidine, from an older class of drugs known as alpha blockers. These drugs block nerve pathways to slow the heart rate.

Godden didn't like clonidine. "Sometimes I woke up and found my mouth was so dry that I couldn't even open it hardly, or speak, and you know what a problem that is for me," she said, laughing.

So her doctor switched her to Norvasc, Pfizer's brand of amlodipine, a calcium channel blocker that relaxes blood vessels by interrupting the movement of calcium into nearby muscles.

Godden, now 73, takes Norvasc and a diuretic every day. They hold her pressure to the high 130s to low 140s. And she says she worries a lot more about hypertension than she used to.

Despite the scare, she still trusts Saunders, chief of the division of medicine at Seattle's Northwest Hospital & Medical Center.

But Saunders isn't sure whom to trust. He questions the stream of studies leading to new guidelines urging broader use of new medications.

"In my heart of hearts," he said, "I am concerned that these studies that are telling people that it's best to get down to 120 over 80 are all paid for by drug companies who are trying to sell pills. It makes me uncomfortable. I think the days of getting unbiased information are gone."

Dueling experts

2 panels encourage broader use of medicines, but a third study questions effectiveness, safety of new drugs.

Saunders' fears are on target. In recent years, expert panels from prestigious medical-research organizations such as the World Health Organization (WHO) and the federal National Institutes of Health (NIH) have called for lower thresholds for blood pressure.

High blood pressure: Chronology of drug development and sales

![]() Change a number, create a patient

Change a number, create a patient

Behind each of those panels were the giant pharmaceutical companies that manufacture the new and expensive hypertension drugs.

In May 2003, for example, an NIH panel recommended broader use of hypertension drugs at lower blood pressures. Nine of the 11 authors of the guidelines had ties to the drug companies (see chart).

The drug industry welcomed the new treatment guidelines and marketed them vigorously. Not surprisingly, as doctors followed the new guidelines and treated hypertension at lower readings, sales of the newer drugs increased.

Last year, patients and their insurance companies spent $16.3 billion for blood-pressure pills, up $3 billion from five years earlier.

ACE inhibitors were the third most frequently prescribed class of drugs last year in the United States, and calcium channel blockers were eighth, according to IMS Health, a firm that tracks pharmaceutical sales.

By then, a different group of hypertension experts had announced findings from the largest hypertension study ever. That study — funded solely by the federal government — was known as ALLHAT (Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial).

The landmark study concluded that the newer blood-pressure drugs are less safe, usually no more effective and far more expensive than decades-old drugs such as diuretics.

The study found that lisinopril and amlodipine, two of the drugs Godden was switched to, were no more effective than water pills in preventing deaths.

On the other hand, lisinopril was linked to 60 percent higher frequency of strokes. Amlodipine, which Godden currently takes, was linked to 38 percent more heart attacks and increased rates of suicide and depression.

Virginia Ashby Sharpe, the former director of the Integrity in Science Project of the Center for Science in the Public Interest in Washington, D.C., criticized the new hypertension drugs: "The more expensive drugs add $8 [billion] to $10 billion a year in health-care costs and provide no additional benefits."

Godden's doctor said he had relied on drug-company-sponsored events, usually held at night, for the latest news on drugs in his field.

Such events never alerted him to the higher risks of amlodipine. But he said he did hear about the ALLHAT study at a drug-company-sponsored "feel-good and have-wine" dinner — during which industry representatives attacked the study's findings.

A world at risk?

Nearly half of the world's population now classified as hypertensive or prehypertensive.

More people visit doctors for hypertension than for any condition other than the common cold. And no wonder, as the threshold for hypertension has dropped from 160/100 to 140/90 and now, with prehypertension, to 120/80.

More than 50 million Americans are considered hypertensive, meaning blood pressure of 140/90 or higher. Additionally, 45 million U.S. adults are said to have prehypertension — a level of 120-139 (top number) or 80-89 (bottom number).

Many heart-disease experts defend the idea of treating prehypertension, saying people need to be warned about the condition because cardiovascular disease usually gets worse with age and patients can benefit from early warning and drug treatment.

Last month, a panel of the American Society of Hypertension also suggested that people with normal blood pressure but other risk factors — age, weight, smoking, family history — be considered to have hypertension and be treated accordingly.

Nearly half the world's population is now classified as hypertensive or prehypertensive, including three-quarters of the elderly population.

Global guidelines

Nearly every member of WHO panel had close financial ties to drug firms.

How did those lower thresholds get set?

The process began in Geneva at the headquarters of the World Health Organization.

Established by the United Nations in 1948, the WHO built its reputation funding research and starting programs to fight malaria and other communicable diseases.

In the 1980s, the agency turned its attention to noncommunicable diseases. But its ability to do meaningful work was limited by a budget that had been frozen at $450 million.

That's where drug companies stepped in.

The WHO solicits tens of millions of dollars yearly from companies whose fortunes it directly affects. In fact, the international agency now takes in more private money — more than $500 million a year — than it gets in dues from its 192 member nations.

WHO spokesman David Porter insisted that the agency doesn't give special treatment to drug companies for their donations, other than good publicity. But the drug companies' internal documents speak of using their donations to open doors and influence policy at the WHO. An internal WHO report first obtained by The Guardian newspaper in 2003 discussed "undue influence" on guideline panels about diets and food additives.

Daphne Fresle, a former top official in the WHO office that monitors worldwide pharmaceutical use, resigned in protest in 2002, complaining of the agency's relationships with drug makers. She said WHO higher-ups routinely censored internal disagreements among staff members over drug-company influence on the agency.

The WHO hypertension guideline is a case study in drug-company influence.

In 1998, the WHO set out to advise doctors worldwide on how to treat high blood pressure. Since the agency had only one doctor assigned to the global study of cardiovascular-risk factors, it turned for advice to experts at the World Heart Federation.

Together, the two groups named Dr. Alberto Zanchetti, an Italian cardiologist, to head the effort to examine and update guidelines for hypertension. Zanchetti appointed the other 17 members of the committee.

All but one of the 18 members had close financial ties to drug firms.

Zanchetti's credentials are as impressive as his industry connections. A professor of medicine at the University of Milan, he founded the European Society of Hypertension and edits the Journal of Hypertension.

He also serves as scientific director of the private Auxologico Institute of Milan, which has 500 beds in three hospitals for doing studies funded by Bayer, AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline and Bristol-Myers Squibb.

He is paid to consult and give speeches for Recordati, Italy's largest drug company, which sells a blood-pressure drug available in 43 countries and awaiting approval in the United States. Zanchetti also took grants or consulting fees from 18 other drug companies, including most of the world's largest. The WHO did not require him to disclose how much money the industry pays him.

The other doctors he appointed to the advisory committee had similar connections, including:

• Dr. Lennart Hansson, from Sweden, who held an endowed professorship at the University of Uppsala that was entirely financed by 10 drug companies and created especially for him. Hansson died in 2002.

• Dr. Giuseppe Mancia, from Italy, who took grant money or speaking fees from 12 drug companies and whose hypertension study for Bayer was widely challenged. Zanchetti named him chairman of the committee.

This guidelines committee met behind closed doors in Fukuoka, Japan, in October 1998. From the start, according to other members of the group, Zanchetti, Hansson and Mancia insisted on lower blood-pressure targets and made sweeping statements endorsing the safety of newer drugs.

Some outside experts were outraged. Dr. Arne Melander, a Malmo University professor and chief of Sweden's government Network of Drug Epidemiology, thought the committee intended to produce only one result: recommending more use of expensive new drugs.

"I got disturbed when I started looking into this, that so few people could influence so much, and that these megaphones for the pharmaceutical industry had become more powerful," Melander said.

"Study after study was carried out by Dr. Hansson, Zanchetti and the group, hoping for something that would finally give evidence that the newer drugs were better," Melander said. "It was shameful."

The resulting 1999 WHO hypertension guideline was remarkable in two ways. It recommended that doctors, as a first course of treatment, pick from any of the five classes of hypertension drugs. Zanchetti and company also proposed 80 as the ideal number for diastolic pressure, the second number on a blood-pressure reading. Anything higher was unhealthy.

The new guideline was an ideal marketing tool for drug companies.

AstraZeneca, a sponsor of Hansson's research, was so excited that it jumped the gun and called a news conference in London to announce the new guideline even before the WHO did.

The WHO distanced itself from the news conference but supported the new guideline — despite a protest signed by 888 doctors, pharmacists and scientists from 58 countries. Their petition said the committee had misrepresented medical evidence and the WHO had "failed its responsibility" to improve care and prevent unnecessary deaths.

Zanchetti, in an e-mail to The Seattle Times, said the guideline was "all supported by published references, so that, at the end, it will be the readers' decision whether the available information has been presented fairly and critically. It is also recognized that, as in all scientific matters, dissension is possible and fruitful."

Zanchetti also said the committee members had disclosed their potential conflicts of interest, including naming companies from which they received funding. However, they did not have to disclose the amounts of money they received or stock they owned.

Many leading scientists say they simply could not do their work without drug-company funding.

The Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA) says its 48 member companies invest billions of dollars in research and marketing to "lead the world in the search for new cures to the most debilitating and deadly diseases."

PhRMA President Billy Tauzin, a former congressman from Louisiana, recently termed it "a responsibility that our industry shoulders for much of the world."

U.S. standards

American guideline writers also closely tied to pharmaceutical industry.

Meanwhile, back in the United States, drug companies were pushing for new domestic treatment guidelines and broader definitions of hypertension that would expand the population of the sick in this country.

Treatment guidelines sprang up in the 1980s, supported by the National Institutes of Health, medical societies and insurance providers, as a way to give doctors standardized advice on the best, most efficient ways to treat a disease and what drugs to prescribe or avoid. The guidelines influenced what care private and government insurers would pay for.

Created to hold down costs, the guidelines now are being used by drug companies to encourage people to spend more money.

The key U.S. guideline-writing panel for hypertension was the one whose advice in 2003 persuaded Godden's doctor to give her more pills.

Among the drugs the panel recommended were fast-acting calcium channel blockers. These drugs were the buzz of the business, lauded in medical journals. As it turned out, the authors of journal articles supporting calcium blockers had financial ties with drug manufacturers, according to a 1998 study in The New England Journal of Medicine.

At the same time, many doctors and researchers without drug-company ties expressed concern about the potential long-term impacts of the calcium blockers.

And although the FDA had approved these drugs, it did not require their manufacturers to prove that the new drugs were more effective or safer than older blood-pressure drugs. Nor did the FDA require that the new drugs save more people from heart attacks or strokes than were lost to the drugs' side effects.

Critics say those shortcomings in the FDA drug-approval process are the reason many pills are later pulled off the market as unsafe.

Spinning the results

Drug firms use several tactics to counter study that undermines their products.

The safety of the new hypertension drugs had concerned the scientists and physicians who launched the landmark ALLHAT study.

It was the gold standard of medical research: long-term, patients selected at random, and neither doctors nor patients knowing who was taking placebos or the real drugs. The eight-year study, which cost $120 million, followed 42,218 Americans for five years to see how they fared on the five classes of hypertension drugs. Final results were published in The Journal of the American Medical Association in December 2002.

The study proved clear-cut advantages for diuretics, said Dr. Paul Whelton, head of the study team and senior vice president for health sciences at Tulane University. All the newer, patented drugs had worse outcomes for heart attacks or strokes, he said.

A pharmacy newsletter summarized it this way: "Salt and water undermine $33 billion hypertension market."

"The question is: Having done this very large and very good study, are we going to respond to the science?" Whelton said.

Some drug companies, upset with the findings, struck back. First, drug companies selectively pulled pieces from the mountain of data produced in ALLHAT and spun them to their own purposes, the researchers say. Pfizer, the world's largest drug maker, responded with a full-page ad in The Journal of the American Medical Association headlined, "ALL HATs off to Istin."

The ad touted Pfizer's $4-billion-a-year blockbuster brand of amlodipine: "Istin in high-risk hypertensive patients is now proven to be equivalent to a diuretic in stroke outcome."

True enough. But what that ad didn't mention: Istin was linked to nearly 40 percent more heart failures.

"Through closer eyes, you see they don't say there's a 40 percent increase in heart failure, and they don't say it's 20 times more expensive," says Dr. Curt Furberg of Wake Forest University, a leader of the ALLHAT study. "That's how they market the guidelines — by omission. How convenient."

Amlodipine is the drug Jean Godden takes to lower her blood pressure.

The drug industry also went on the attack against some of ALLHAT's key researchers as well as against Dr. Bruce Psaty, a public-health professor at the UW wrote about the findings. He does not take industry money to support his research.

Several academic consultants to drug makers — without disclosing company ties — publicly attacked Psaty's scientific integrity.

"It was very intense," Psaty said. The dean of his department defended him and his research.

Despite the battering, Psaty as well as Furberg and the ALLHAT researchers stood firm: It was indisputable that many patients have been sold pills that can lead to more strokes or heart attacks than cheaper, safer, time-tested alternatives.

Despite the scientific proof, diuretics and beta blockers will continue to lose their share of the blood-pressure-medicine market, dropping 35 percent and 52 percent, respectively, from 1998 to 2007, according to industry forecasts.

Diuretics aren't even available in most countries because drug companies don't push them, said Dr. Shanthi Mendis, head of the cardiovascular-disease program at the WHO.

The reason: Diuretics cost pennies a day and bring minimal profit, so drug makers have little economic interest in promoting this cheap, effective treatment.

Wake Forest's Furberg says the 700 doctors who worked on ALLHAT will continue to try to disseminate their guidelines about treating hypertension through universities, pharmacies and at local meetings, reacquainting doctors with the benefits of water pills.

"We have a long way to go until they are No. 1," he said.

Duff Wilson reported and wrote this story while working for The Seattle Times. He now reports for The New York Times. Send comments to suddenlysick@seattletimes.com or call 206-464-2508.

Entertainment | Top Video | World | Offbeat Video | Sci-Tech

general classifieds

Garage & estate salesFurniture & home furnishings

Electronics

just listed

More listings

POST A FREE LISTING