Originally published June 5, 2010 at 10:00 PM | Page modified June 5, 2010 at 10:03 PM

![]() Comments (0)

Comments (0)

![]() E-mail article

E-mail article

![]() Print

Print

![]() Share

Share

Larry Stone

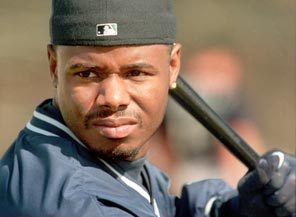

Ken Griffey Jr. in his prime will be the sight to remember

As time passes, the napping controversy, the painfully low production numbers, the abrupt decision to pack up and head home, all the distress from Griffey's desultory 2010 partial season will fade into oblivion.

|

Seattle Times baseball reporter

Roger Jongewaard doesn't want to dwell on the awkward ending to Ken Griffey Jr.'s career, which grinded to an uncomfortable halt on Wednesday.

Jongewaard prefers to think about Griffey's glorious beginnings.

It was Jongewaard, as the Mariners' scouting director, who made the recommendation in 1987 to select the high-school outfielder from Cincinnati's Moeller High School with the No. 1 overall pick.

Granted, it didn't take a baseball Einstein to recognize the burgeoning phenomenon that was Griffey. But Jongewaard had to convince skeptical M's owner George Argyros that Griffey was the right man. Argyros, it seems, was still irked about the slow progress of Jongewaard's previous year's No. 1, outfielder Patrick Lennon.

"I told him I wanted to take Junior," recalled Jongewaard, now 74 and living near San Diego, where he scouts for the Florida Marlins. "He said, 'No, there's a college pitcher from Fullerton I think is better suited for us, Mike Harkey.'

" 'No, Junior's the guy,' " Jongewaard assured Argyros.

" 'That's what you said about the last guy,' " the owner replied.

Jongewaard ultimately won that debate, and the rest is baseball history and Seattle legend.

As time passes, the napping controversy, the painfully low production numbers, the abrupt decision to pack up and head home, all the distress from Griffey's desultory 2010 partial season will fade into oblivion.

Or, at worst, it will fade to obscurity, hidden on some dark shelf in the attic, while his glittering body of work shines in the sun.

After all, does anyone downgrade Babe Ruth because he hit .181 his final year, at age 40 with the Boston Braves, feuded with management, and had teammates who refused to pitch if he played the outfield?

Does anyone mark down Willie Mays because of his stumbling final days with the Mets?

![]()

Is anyone's memory of Mike Schmidt diminished because he, like Griffey, hung on one year too many and walked away in May 1989, embarrassed by his limp .203 batting average?

Of course not. The truly great ones transcend their denouement, no matter how distressed, and are seared in our memory banks as perpetually young, vibrant and in full command of their skills.

At least Griffey went out with some symmetry: He retired 75 years to the day after Ruth did, and 23 years to the day after the Mariners called his name in the '87 draft. And his last official appearance, a fielder's choice as a pinch-hitter against Minnesota on May 31, occurred 19 years to the day after his father, Ken Griffey Sr., played his last game, also as a Mariner.

Griffey Jr. always had a certain flair, but if he left in a bit of a huff, it was in step with the hypersensitivity that permeated his career. Griffey was, for the most part, a joyous personality and an infectiously positive presence. Yet when he seethed, you knew it.

Jongewaard recalls watching Griffey for the very first time at the Connie Mack World Series in New Mexico, when even as a 16-year-old he was so dominant that pitchers routinely pitched around him. When the intentional walks became incessant, Jongewaard recalled, Griffey defiantly put his bat behind his head as the pitches were in progress.

"A lot of scouts were really upset because of that," Jongewaard said. "I thought, 'Well, that's good, because they won't take him even if they draft ahead of us.' "

Griffey's limitless potential was evident literally from day one, when he showed up at the Kingdome to take ceremonial batting practice with the Mariners shortly after the draft.

"He jumped into the cage and he was hitting more home runs than Alvin (Davis)," Jongewaard remembered. "He looked like the best hitter we had. Most kids in that situation are scared to death. He was used to being in major-league stadiums. He was completely comfortable."

It was Jongewaard who drove Griffey up to Bellingham for the start of his professional career. Jongewaard invited him to breakfast one morning.

"He said, 'I don't eat breakfast. I'm kind of a junk-food guy, Twinkies,' " recalled Jongewaard. "He had a great body, of course. I said, 'Holy cow, he doesn't even have to work at it.' "

Some believe that Griffey would ultimately pay a heavy price for a laissez-faire attitude toward fitness as his career progressed, but the fact his body broke down though all those injuries was probably more attributable to his time on the hard Kingdome turf.

The fact that Griffey's decline followed what used to be a standard timeline before the freakish extension of the prime of some players, most notably Barry Bonds and Roger Clemens, merely strengthens the prevailing sense that Griffey steered clear of performance-enhancing drugs.

In his biography of Bonds, "Love Me, Hate Me," author Jeff Pearlman recounts a dinner conversation between Bonds and Griffey after the 1998 season.

As Pearlman describes it in the book, Bonds told Griffey, "As much as I've complained about McGwire and Canseco and all of the bull with steroids, I'm tired of fighting it. I turn 35 this year. I've got three or four seasons left, and I wanna get paid. I'm just gonna start using some hard-core stuff, and hopefully it won't hurt my body. Then I'll get out of the game and be done with it."

Griffey is quoted in the book as saying: "If I can't do it myself, then I'm not going to do it. When I'm retired, I want them to at least be able to say, 'There's no question in our minds that he did it the right way.' I have kids. I don't want them to think their dad's a cheater.' "

I e-mailed Pearlman and asked him if, in the course of researching the Bonds book, he became convinced that Griffey was clean.

"If you had asked me three or four years ago, I would have said yes, definitely clean," he answered. "But I don't give the 100 percent-beyond-a-doubt status to anyone anymore, including Griffey. Do I hope he was clean? Yes. Do I believe he was clean? I guess probably. But it'd be naive to be convinced about anyone. Even him."

That's a justified response in this era, though I have never found cause to question Griffey's legitimacy, nor has anyone in baseball I've ever spoken to. A Mariners teammate, Norm Charlton, recalls watching Griffey's raw power manifest itself even as a teenager, when he would come work out at Riverfront Stadium while Charlton was pitching in the Reds' organization.

"I don't even question that," Charlton said. "I wouldn't even put Junior in that category. It's a no-brainer for me."

Griffey's minor-league stay would last just 129 games before the Mariners threw away any pretense of more seasoning and put the 19-year-old Griffey where he belonged — on the major-league roster to start the 1989 season.

His penchant for dramatics was immediately shown when he doubled in his first major-league at-bat, off Dave Stewart, and homered on the first pitch he saw at the Kingdome, off Chicago's Eric King. You couldn't script that kind of stuff.

Oh, you could have scripted a better ending for Griffey, one in which he rode off into the sunset (or was carried off on his teammates' shoulders, ahem).

But that's just a temporary blot. The Junior portrait that will survive the test of time has his hat backward and a huge smile on his face. The Junior video we will replay in our mind is a Hall of Famer in his absolute prime.

Larry Stone: 206-464-3146 or lstone@seattletimes.com

UPDATE - 10:00 PM

Larry Stone: Young pitcher Michael Pineda offers glimpse of exciting future for Mariners

Larry Stone gives an inside look at the national baseball scene every Sunday. Look for his weekly power rankings during the season.

lstone@seattletimes.com

Entertainment | Top Video | World | Offbeat Video | Sci-Tech

general classifieds

Garage & estate salesFurniture & home furnishings

Electronics

just listed

More listings

POST A FREE LISTING