Originally published April 1, 2014 at 9:29 PM | Page modified April 2, 2014 at 4:27 PM

Slide erased their homes, but maybe not their loans

In the aftermath of the Snohomish County mudslide, surviving homeowners face the possibility having to repay mortgages on homes that no longer exist.

Seattle Times business reporter

Resources

Handling finances after a natural disaster:

dfi.wa.gov/consumers/natural-disasters.htm

Facts about landslide insurance:

www.insurance.wa.gov/your-insurance/home-insurance/landslides/

Does Fannie Mae own your mortgage?

Oso landslide: Comprehensive coverage of the March 22 disaster and recovery

The Seattle Times

A collection of stories and visuals about the disaster, why it may have happened and the people it affected.

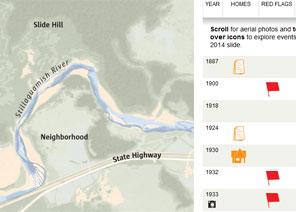

Interactive: Building toward disaster

THE SEATTLE TIMES

Use an interactive to see how, even as warnings mounted, homes kept being built in slide-prone Steelhead Haven.

Remembering the victims

Compiled by The Seattle Times

Read about the lives of the victims.

Interactive map: A detailed view of the neighborhood hit by the landslide

Garland Potts, Cheryl Phillips / The Seattle Times

Use an interactive tool to see the landslide’s deadly path.

TIMES WATCHDOG

![]()

A community bank with branches on both sides of the Snohomish County mudslide says it’ll forgive uninsured debts for customers affected by the catastrophe.

But bigger banks aren’t offering a blanket reprieve, leaving homeowners — many of them with large mortgages — in financial limbo.

“It’s really going to take all of the banks helping to get that market back on its feet,” said Eric Sprink, CEO of Everett-based Coastal Community Bank, which has branches in Arlington and Darrington . “If insurance doesn’t help them, Coastal stands ready and willing to write off our debt.”

More than a week after the March 22 mudslide, which destroyed dozens of homes and killed more than two dozen people, the survivors and families of the dead are left to grapple not just with emotional losses, but financial ripple effects too — including debts on houses and autos chewed up by the mile-long landslide, one of the worst natural disasters in state history.

A preliminary damage assessment by state and federal agencies offers new details on the scale of the devastation: Thirty of 42 homes in the destroyed neighborhood were primary residences; none of the 30 had landslide insurance and almost all of them belonged to low-income families. The average market value of the destroyed homes was $164,717.

“A complete loss of real estate is unique for Washington disasters,” Gov. Jay Inslee wrote Monday in a letter asking President Obama to designate the mudslide a “major disaster,” triggering federal aid to individuals. “After an earthquake, tornado or flood, victims may have lost their homes, but they are able to rebuild; the residents of Oso will likely not have that option.”

Contaminated soil, widespread flooding and a rerouted Stillaguamish River have left many homeowners uncertain whether they’ll ever be able to reclaim their land. While a government buyout of the property could provide relief, Inslee stopped short of saying the state will pursue that option.

Most of the homeowners displaced by the mudslide still have outstanding debt.

“The most important thing people can do is call their bank and ask, ‘What do we do?’ ” Sprink said. “They need to start asking the hard questions of their banks and insurance companies to get some answers so they can make some tough decisions.”

Public records show a wide range of original debt on the properties, with the most expensive being a $625,600 loan taken out in 2011 by Sandy and Larry Miller, who at the time of the slide were building their dream house on the river. The Millers are among those missing.

Because mortgages are legally binding contracts, homeowners are still responsible for full repayment of the loans, even if the homes are gone, said Lyn Peters, a spokeswoman for the state Department of Financial Institutions.

The state is advising survivors of the mudslide — or in some cases, the heirs of those who died — to call their banks to work something out.

But those who do might not get a quick resolution because the banks often don’t own the loans; investors do, and Fannie Mae, the government-sponsored enterprise, is one of the biggest.

Fannie Mae says it permits banks and other mortgage servicers to give homeowners in federally declared disaster areas a “forbearance,” or temporary break on making payments, for as long as 12 months.

If survivors can’t get adequate relief on their mortgages, Sprink said, they may pursue bankruptcy to get rid of the debt. But that option casts a long shadow.

“Why ruin their credit?” Sprink said. “Either way, the bank and investors are going to lose. Where does common sense come into this? People have got to be talking out loud about this.”

Officials from JPMorgan Chase, Wells Fargo and Union Bank, all of which made loans to homeowners in the area, declined to say whether they would consider canceling debts on homes destroyed by the mudslide.

Several big banks, including Chase and Wells Fargo, have pledged tens of thousands of dollars to disaster relief. They’ll also look at individual borrowers’ circumstances.

“Our hearts go out to the people of Oso, Arlington and Darrington and we intend to work with homeowners on a case-by-case basis since every homeowner may be in a different situation,” Union Bank’s Seattle-based spokesman Alan Gulick wrote in an email.

Lara Underhill, a Seattle-based spokeswoman for Wells Fargo, said homeowners can receive a 90-day reprieve on mortgage payments only after an area is designated a major disaster area.

For credit union BECU, writing off debt “will certainly be part of our consideration in helping our members recover after this devastating event,” spokesman Todd Pietzsch said.

But canceling a debt can have negative consequences too: With few exceptions, the forgiven debt is counted as taxable income under the federal tax code.

Homeowners desperate to cover their costs could receive as much as $32,400 from the federal government if Obama approves a “major disaster” declaration, said Karina Shagren, a spokeswoman for the Washington Military Department.

But, “It’s possible that some of those outstanding loans exceed that,” she said.

Insurance gaps

Insurance can help recoup some financial losses, but standard homeowners policies don’t cover losses caused by landslides, floods or earthquakes.

Mortgage life insurance and catastrophic disability mortgage insurance are designed to pay the remainder of the mortgage if the borrower dies or is disabled, said Peters, of the state Department of Financial Institutions.

Alternatively, homeowners can buy a “difference-in-condition” policy that offers some protection against earthquakes and landslides, said Karl Newman, president of the NW Insurance Council. Only 4,700 homes and business owners in Washington have bought policies to protect against landslides, he said.

“There are thousands and thousands of people in Western Washington at risk of this, but only a few have taken out a policy to protect them against this risk,” Newman said.

But there’s a catch: If you live in an area known to have a high potential for landslides, you probably can’t get the insurance, said Sandi Esparza, a manager at Hub International Northwest, a Bothell insurance brokerage.

“You need to buy it before your area erodes and you need it,” she said.

The cost of a policy depends on several factors, including the value of a home, its distance from a hillside and evidence of slides nearby. A policy on a $350,000 home can cost about $1,000 a year with deductibles ranging from 10 to 20 percent, she said.

Flood insurance has long been required under federal law when financing a home in a high-risk flood area.

But there’s no requirement for landslide insurance.

“Will that change now that this has happened?” Esparza wondered, referring to the Oso tragedy.

A slide on the same hill in January 2006 raised safety concerns, but that didn’t stop banks from approving mortgages in the area. Public records show the latest slide destroyed 21 homes whose owners received their loans after the 2006 slide.

While some homeowners there had flood insurance, that might help only those whose homes flooded when the river backed up behind debris from the slide. Those whose homes were destroyed by the mudslide itself may not be covered by the insurance.

According to the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), flood insurance protects against mudflows but not mudslides. The difference? A mudflow has the consistency of a milkshake, FEMA says, while a mudslide is more solid like a cake.

The Oso event, a FEMA official said, was a mudslide.

Land buyouts

If President Obama approves Inslee’s request, the state may receive funding for “hazard mitigation,” a broad category that officials say could be applied to projects beyond Oso, as long as they are designed to minimize the impact of natural disasters, including floods and earthquakes.

Still, “No decision has been made whether that funding — if we receive any — will be used specifically for land buyouts,” said Shagren, the state Military Department spokeswoman.

Since 1993, communities around the nation have bought out more than 20,000 properties in disaster areas — including about 500 in Washington — to prevent future damage. FEMA covers 75 percent of the cost.

In such cases, local communities acquire title and clear the land to create open space. Property owners receive up to the fair market value of their property before the disaster, according to FEMA’s website.

But after a 1998 landslide in Kelso, in southwest Washington, damaged more than 100 homes — it was one of the worst landslides in U.S. history at the time — property owners who received buyouts got only about 30 cents on the dollar.

In Inslee’s letter to Obama this week, he stressed that the survivors of the Oso landslide will likely never return home.

“Not only are their houses and household effects gone,” he wrote, “but the land itself is gone.”

That point was underscored by John Parduhn, who about two years ago sold a vacant, quarter-acre lot in the slide area to his next-door neighbor, Seth Jefferds. Jefferds, a volunteer firefighter, lost his wife and granddaughter in the disaster.

Parduhn loaned Jefferds $20,000 at the time of the sale. But he’s not worried about collecting what he’s owed — especially knowing so many have lost everything they had.

“For me it’s minor compared to them,” he said. “Everything’s changed up there. You won’t be able to recognize it.”

Sanjay Bhatt: 206-464-3103 or sbhatt@seattletimes.com On Twitter @sbhatt

Four weeks for 99 cents of unlimited digital access to The Seattle Times. Try it now!

Four weeks for 99 cents of unlimited digital access to The Seattle Times. Try it now!