Originally published January 22, 2012 at 6:00 PM | Page modified January 25, 2012 at 3:40 PM

Waiting on predator island: Chronic delays drive up cost

Sex offenders who face civil commitment at McNeil Island routinely postpone their trials for years, driving up costs and wasting state money. In King County, each case can cost up to $450,000.

Seattle Times staff reporter

DEAN RUTZ / THE SEATTLE TIMES

"MADHOUSE": The Special Commitment Center on McNeil Island houses 284 of the state's most dangerous sex offenders. For more than a century, the island in south Puget Sound was home to a penitentiary, which the state closed in April 2011.

DEAN RUTZ / THE SEATTLE TIMES

"If the men living here were released, there is no doubt in my mind that we would have a multitude of new victims."

DEAN RUTZ / THE SEATTLE TIMES

RED FLAGS: Molester Raymond Marshall knows what to avoid if he's ever released: "Baby-sitting, parks, fairgrounds, malls, movies ... also being around small kids."

DEAN RUTZ / THE SEATTLE TIMES

NOT QUITE A PRISON: An offender's behavior and treatment progress can affect his access to amenities.

DEAN RUTZ / THE SEATTLE TIMES

INSIDE THE SCC: The center includes a medical clinic, dentist office and spaces for people to practice their religions, participate in board games or play sports or music.

DEAN RUTZ / THE SEATTLE TIMES

BARBER SHOP: Chris Cantley, a resident, gets a haircut in the commitment center.

Rapist Eddie Williams says he's "a thug," not mentally ill, and therefore shouldn't be at McNeil Island.

Eddie Williams

Part One: Expert Costs

State wastes millions on sex-predator legal bills

Sex offenders' legal costs were kept secret from public

Timeline: Evolution of Washington's troubled civil-commitment program

Graphic: How a sex offender gets committed to McNeil Island

Expert costs: source documents

Part Two: Predator Island

Waiting on predator island: Chronic delays drive up cost

Sex offenders could get trials annually, driving up the legal bills

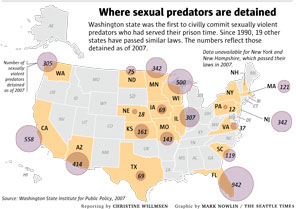

U.S. map: Where sex predators are detained

Predator island: source documents

Part Three: Worst Case

Swayed by a psychologist, jury frees 'monster' who attacks again

Part Four: Challenges

Tiny office says it can save state money on sex-offender defense

![]()

McNEIL ISLAND, Pierce County —

Convicted rapist Eddie Williams admits he's a "thug." But he insists he can control his urges and shouldn't be locked up in the Special Commitment Center.

Even so, Williams and his taxpayer-funded lawyers delayed his civil-commitment trial for 11 years — racking up legal bills as he continued to be held inside the SCC, a place he loathes and calls a "madhouse."

In fact, sex offenders like Williams routinely postpone their trials for years, driving up costs and wasting money.

Their defense lawyers seek multiple continuances and file challenges to Washington's civil-commitment law, which allows the state to lock up the most dangerous sex offenders after they complete their prison sentences. Scheduling conflicts among lawyers, far-flung forensic experts and judges also contribute to delays.

Taxpayers foot the bill, paying for both sides of the case, including state attorneys, defense lawyers, paralegals, investigators and psychologists. Last year, the Special Commitment Center spent $12 million — almost a quarter of its budget — on legal bills.

King County has the distinction of having the slowest and most expensive civil-commitment trials in the state, with recent cases taking on average 3.5 years to reach a jury verdict, records show. One current case has been delayed for 10 years, so far.

David Hackett, the King County prosecutor who manages its civil-commitment cases, blames defense lawyers for delay tactics, making some cases cost up to $450,000.

"I can think of a handful of cases where we've asked for continuances," he said. "The remaining hundreds of continuances are at the request of the defense."

Kenneth Chang, a lawyer at The Defender Association who represents sex offenders, said on paper it looks like the defense is asking for all the continuances, but the state typically agrees with the delays.

"The state will suggest, 'We're not going to ask for a continuance, but if you ask for it we won't object' — wink wink," he said.

"There is a public interest of trying to get these resolved, and I believe that needs to happen sooner than later."

Delays often take so long that lawyers take new jobs or are reassigned. Experts move on or have to update their psychological evaluations of an offender. Each new person must learn the case and its stacks of documents, taking more time and money.

The state has no accounting system to determine the costs of an individual case.

Hackett came up with an estimate for how much delays can cost. "When the trial rolls around eight months later you probably have spent another $70,000 or $80,000," he said.

Multiply the costs of delay by dozens of cases, year after year, and the public is on the hook for a mountain of extra spending.

"I don't think that anybody anticipated when this law was codified that it would cost this much," Kelly Cunningham, superintendent of the Special Commitment Center, said of Washington's 1990 civil-commitment law, the nation's first.

The state pays defense lawyers by the hour, which may take away a financial incentive to be efficient.

A Snohomish County public defender, Martin Mooney, said some sex offenders drag out their trials because they know chances are high they'll lose in court and be declared a "sexually violent predator." Once officially committed, they face even slimmer chances of winning release from the SCC.

"They serve long, long prison sentences and the last few years of their sentence they get petitioned" to be committed to the SCC, Mooney said. "They are beaten down. Their level of hope is so low that they are not in a rush. It's no longer urgent."

Delay tactics

Eddie Williams presents a case study of costly delay.

In 1999, just as Williams was set for release from prison, King County prosecutors filed a petition to have him committed as a sexually violent predator, or SVP.

He was just 13 when he first raped a woman. As an adult he continued to sexually assault women and heavily abused drugs. One psychologist described Williams as having a Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde personality, saying he "may seriously injure or kill a female victim or anyone who may seriously challenge or thwart him."

In a phone interview from McNeil Island, Williams, 52, said he chose to commit those sexual assaults, but now feels remorse. He added that he's just a criminal who can decide to stop at any time.

"I do represent the word 'thug,' " he said. "I'm not no mentally ill SVP that do not have control over myself."

Early in the case, a lawyer for Williams argued for release, claiming he was a victim of double jeopardy, being punished for the same crimes twice. In addition, the lawyer argued, being held at the SCC was worse than being in prison. The judge ruled against them.

Williams also refused to be evaluated by a state psychologist, creating more delay. The prosecutor had to get a court order, forcing him to participate.

In spring 2006, his lawyers quit his case for unstated reasons. It was delayed for 14 months so two new lawyers could prepare his case.

Civil-commitment cases take more work than most serious criminal cases. Lawyers and experts must comb through thousands of pages that document an offender's life and institutional history, and review studies on recidivism and mental disorders.

Weeks before trial, Williams' lawyers asked for and were granted another continuance, saying they hadn't been able to work on the case over the past year and still needed to pick a psychologist.

The prosecution agreed to another continuance only if Williams and his defense lawyers promised it would be the last. But the defense asked for and was granted several more.

Lin-Marie Nacht, one of Williams' lawyers, explained to the court that they needed more time because Williams, despite a normal IQ, had trouble processing information and had a far-below-average working memory.

A trial was set for March 2008 but then the prosecution's expert wasn't available for that time and the defense said it still hadn't hired an expert. Another delay occurred because Williams was being treated for prostate cancer.

In total, he had eight different defense lawyers and 11 continuances, and faced several different prosecutors. "I was basically just fighting my case and preparing my case for court," Williams explained.

Nacht declined to be interviewed.

Delays can help a sex offender's defense.

The older he becomes, the lower his risk of perpetrating new sex crimes, forensic psychologists believe.

Over time, the state's forensic psychologists also may change their opinion about confining an offender.

For example, the King County Prosecutor's Office has dismissed seven cases because its experts, after delays of a year or two, changed their minds about whether the offenders continued to meet the criteria for commitment: The offender has a mental abnormality or personality disorder, which makes him more likely than not to commit a violent sex crime if released.

In fact, since 1996, 52 sex offenders have spent anywhere from a couple of months to several years at the SCC before the state either dismissed its cases against them or lost at trial.

Delays also make it harder for the state to track down victims to testify. For example, Williams' crimes took place as long as three decades ago; the victims, now in their 70s, were having health problems or were reluctant to testify.

For this reason, prosecutor Alison Bogar opposed any more continuances, saying it "would almost certainly result in additional victims being unable to testify as well as an increase in costs of expert witness fees."

But a judge granted the continuance. In May 2010 the case finally went to a jury. It took about four hours to determine that Williams was a sexually violent predator.

His attorney appealed, which is typical.

According to an analysis by The Times of committed SCC residents, 73 percent filed appeals. Of those, each filed on average three or four appeals. One offender, Darnell McGary, has filed 23 appeals.

Caught with porn

Cecil Baiz, 52, a convicted child molester held at McNeil Island for 10 years and counting, has yet to have his civil-commitment trial.

Prosecutor filed against him in August 2001, after a state psychologist determined, among other things, that Baiz was a pedophile. He was convicted in 1995 of first-degree child molestation of a 9-year-old girl at a playground.

Over the decade, he has had 11 defense attorneys. Four different prosecutors have been assigned to his case. In all, judges have granted 16 continuances, almost all at the request of the defense.

Defense lawyers repeatedly have challenged the constitutionality of the commitment law to the Washington Supreme Court.

Attorneys for Baiz and other offenders have used these pending appeals as a reason to ask for continuances, arguing that an upcoming decision may benefit their clients.

"Consistently, his attorneys have gone to the court and indicated Mr. Baiz doesn't want to go to trial yet," Hackett said.

Baiz had no comment. Devon Gibbs, one of his public-defense attorneys, said she couldn't discuss details of the case.

By 2008, the forensic expert hired by Baiz's lawyers said more time was needed to update the original evaluation, which was several years old, according to court records.

Throughout all this, Baiz was collecting child pornography on his computer at the SCC, according to court records, including several images "of known and identified child victims."

The FBI and the US Postal Inspection Service are investigating, and Baiz may soon face federal charges.

Due to the new evidence, Baiz's commitment trial was postponed, again, this time to March.

Hackett tried to curb continuances last year through legislation. But the bill went nowhere after judges opposed it.

Life on the inside

There's only one way to get on McNeil Island — a high-security ferry. Once dropped off at the shore, approved visitors must take a bus that winds past miles of deep woods into a clearing where the SCC was built eight years ago.

With McNeil's penitentiary closed since April, the SCC remains the only thing on the island.

Past the guards, cameras and concertina wire, live 284 sex offenders, with 66 of them yet to be officially committed.

"This is the cesspool of cesspools," said Ricardo Capello, whose case took six years to go to trial. He said dangerous residents live there and some of the staff are corrupt.

"If you were to tour it, they will put on a good dog and pony show here."

Cunningham led The Times through the center, where guards and staff are distinguishable from offenders by their green shirts, black pants and white name tags. Sex offenders, called "residents," wear casual clothing like jeans and T-shirts. Depending on their behavior and progress in treatment, residents are allowed access into different areas of the $60 million compound.

The center has a medical clinic, dentist office, counseling rooms and even a barber shop. There are rooms for people to practice their religions, join in board games and play musical instruments.

In the gym, an offender hit a punching bag. Down the hall, another worked out on an elliptical machine.

In the woodworking shop, another man had just finished making a bass guitar. Others roamed the landscaped courtyard, smoking cigarettes.

More than 190 cameras keep track of the residents' movements.

"If the men living here were released, there is no doubt in my mind that we would have a multitude of new victims," Cunningham said.

But the state didn't build the center by choice nor did it anticipate needing more than 440 employees to operate it when its pioneering civil-commitment law passed more than 20 years ago.

In 1994, a federal district judge found the state violated offenders' rights by detaining them in a prisonlike environment. The court forced Washington to provide a treatment program that made it possible for them to be released.

"There was no blueprint for civilly committing sex offenders," Cunningham said. "It was trial by error."

In October 2009, the federal injunction was lifted only after the SCC made drastic and expensive improvements.

The civil-commitment program has an annual budget of about $50 million, which includes operation of the main facility, two less-secure facilities and legal costs. It breaks down to $173,000 a year for each resident, he said.

Offenders' living quarters vary by their mental condition and progress in treatment. Individual rooms are larger than prison cells and some have windows, giving it a "college campus" feel, Cunningham said.

During the tour, two men were detained in the Alder Unit — a padded lockdown area — because they were psychotic and smearing feces.

Some offenders at the SCC have been able to obtain illegal drugs, child pornography and other contraband.

In the past four years, the center found 10 sex offenders with child pornography in their rooms or on their computers, which have no Internet access. They were convicted and are currently serving 10-year sentences in federal prison. Another eight residents may be charged, Cunningham said.

"It's no secret it's an ongoing investigation," he said.

Part of the problem has been the staff. Residents claim they can get just about anything they want from employees willing to break the rules. Cunningham said he's fired seven people since 2008 for contraband.

Among those fired: one guard who smuggled crack cocaine into the center, a staffer who took $15,000 from a resident in exchange for pornography, and a nurse who gave him large sums of money and pornography.

"We know we've had dirty staff," he said.

Cunningham, who's worked at the center for 13 years, said since becoming superintendent in 2009 he's tightened security, including searches of staff and X-ray scans of mail.

But problems here are not entirely fixed.

A supervisor, Jamele Anderson, was fired in July for viewing more than 100 pornographic images on an SCC computer.

The Times also discovered that Anderson, who was hired in 2001, was charged with theft and several counts of forgery, according to Pierce County court records. He pleaded guilty in November 2005 to obstructing a law-enforcement officer, was placed on two years of probation and required to pay restitution.

Anderson also was required to notify the SCC of his arrest, but he didn't.

When he was promoted in 2007 to residential-area manager, a required background check didn't pick up the conviction. He still hasn't paid $5,644 in fines and restitution, court records show.

Cunningham said he did not know about Anderson's conviction, but didn't see a need to revise the way the center conducts background checks.

Beyond the unchecked legals bills, the SCC has other financial problems. The Washington State Auditor's Office criticized the SCC for spending $2.6 million for off-island medical services from 2009 to 2011 without getting written contracts and competitive prices.

"We found reasonable cause to determine that the Center's practice of paying for medical services resulted in gross waste of public funds," according to a recent report.

Auditors also are investigating complaints that staffers as well as a contractor were paid for work they didn't perform.

"No cure for this"

Raymond Marshall, a 40-year-old, developmentally delayed child molester, was eager to talk to a Times reporter taking the tour. Marshall said he wasn't safe out in the community, and needed to be committed in 2003.

He admitted having 15 victims, mostly young girls and boys, and that he fantasized about killing, according to court records.

As part of treatment, which is voluntary, Marshall said he's identified situations that he needs to avoid if ever released. He said red flags include: "Baby-sitting, parks, fairgrounds, malls, movies ... also being around small kids."

"I wanted to get more help so I wouldn't hurt no more kids, because I don't want to go out and reoffend again," he said.

While in prison he went through several sex-offender treatment programs and was kicked out or, after being released, reoffended not long afterward.

Researchers and psychologists continue to debate if treatment even works.

"There's no cure for this," Cunningham said. Treatment can help them cope with their personality disorders and teach them ways to avoid reoffending, he added.

Each year, sexually violent predators are reviewed by an SCC psychologist to see if they should remain committed. They also are entitled to a review by their own state-funded psychologist.

If the state cannot show they still meet criteria for civil commitment, they're released into the community.

In two decades, only eight SCC residents have been unconditionally released because they successfully completed treatment. So far, none has been found to have reoffended.

Half the offenders at the center, including Williams, refuse treatment, saying they don't have a problem. That mindset can be bolstered by a defense expert who says they don't have a mental disorder.

Williams says the staff and SCC psychologists can't be trusted. "They gather information about your past, present and future, and use it against you," he said.

Williams spends some of his time dreaming about starting a business, a clothing line, if he's released.

Other times his thoughts wander to ideas of suicide, injustice and rage.

"I was preparing myself for the worst, and the worst is here," he said of his residence for the past decade. "This has made me so angry and ill-minded, so vicious ...

"I think about bad things that I don't want to tell you on this phone that scare me and that scare you."

Christine Willmsen: 206-464-3261 or cwillmsen@seattletimes.com. On Twitter @Christinesea. Researcher Gene Balk contributed to this report.