WHEN WE FIRST MEET Ruth Njawara Chimuonenji, it is late on a Saturday afternoon and the sun has long ago starched the morning laundry dry.

|

| BETTY UDESEN / THE SEATTLE TIMES |

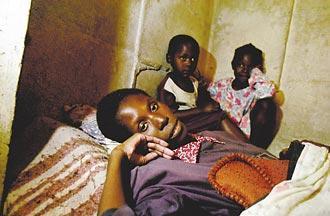

| Ruth Njawara Chimuonenji married an older man who was unfaithful and refused to use condoms. When he died, she brought their children, Tafadzwa and Martha, home to her parentsí tiny, crowded bungalow and peddled small items at the bazaar to help buy food. Then, just 24, she fell ill with AIDS. "Who will take care of my children?" she asked visitors the day before she died. |

|

|

|

She is in bed, under scruffy blankets, in a tiny room of makeshift walls. For two weeks, she's been sick. Stomach running at both ends. Cough. Horrible headache yesterday that today is thankfully gone. She is 24 and gaunt, with hollow cheeks and exhausted eyes. Yet her skin is lovely and supple, her lips young and full. You can tell if she weren't feeling so lousy, she'd greet you with a beautiful smile.

As it is, she weakly presses your hand. Her fingers are cool, as if they've absorbed the dampness of the little cinderblock house.

Ruth moved home to Mabvuku township two years ago, back into the weary bungalow where her parents make room for 10 of their 12 children and several grandchildren. Ruth's husband, a truck driver, had died of tuberculosis in tandem with AIDS. Her in-laws blamed their son's death on shu-shu, witchcraft; they accused Ruth of killing him with evil herbs and magic to get his property. After his funeral, they took everything and left Ruth to raise the two children.

Martha will soon be 6 and loves flowered dresses. Tafadzwa is almost 4 and has eyes that promise mischief, but right now he looks scared. Strangers stare and ask questions. His mother is shrunken and ill. She squeaks like a baby mouse when he bumps against her. She can't gather enough air in her lungs to push out much sound.

"I wish my daughter would grow up to be a big girl, get a proper education and get married to a husband who will take care of her ... Not like what happened to me."

— RUTH CHIMUONENJI, AIDS VICTIM |

|

|

|

|

|

|

"Who will take care of my children?" Ruth whispers.

Her mother and sisters have promised they will, so her question reaches beyond: What will happen to her children if the mealy-meal runs out (a distinct possibility given the current food shortage), if Zimbabwe's government collapses (also possible), if something should befall her mother, if her sisters get AIDS?

Most of all, Ruth worries about Martha. Who will protect her quiet daughter as she becomes a woman? If there is no food, no school, no jobs, what might Martha be forced to do to survive? What if she falls for the wrong man? Who will teach Martha about love?

"I wish my daughter would grow up to be a big girl, get a proper education and get married to a husband who will take care of her," Ruth says, her voice a wisp. "Not like what happened to me."

|

The life expectancy of a child born today in Zimbabwe is 38 years; without AIDS, it would be 70. |

IN SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA, 28.5 million people are infected with the AIDS — more than three times the population of New York City plus all the people in greater Seattle from Everett to Olympia. The world's highest AIDS infection rate is in southern Africa, in the nations of Zimbabwe and Botswana.

In Europe and the Americas, AIDS has most often been passed on through high-risk gay sex and needle-using drug addicts. But in Africa, the disease is largely spread through sex between men and women. In Zimbabwe, as many as a third of adults are infected with HIV.

Most are women.

The culture of sex in southern Africa would appear to put men at greater risk. They typically have more sex partners, before and outside of marriage.

And men do suffer. In the sub-Sahara, 12 million live with HIV.

But men, if they choose, can use condoms to spare themselves infection. Women have no way to protect themselves and no say. About sex. About condoms. About boyfriends and husbands who spread the virus by sleeping around, passing it from girlfriend to lover to wife.

Women account for 58 percent of all new HIV infections. The younger they are, the worse the statistics: Two out of three people infected in their late teens to early 20s are female; adolescent girls are five to six times more likely than boys to contract HIV.

Blame anatomy (women's tissue abrades more easily during intercourse, leaving wounds for the virus to enter); economics (food is scarce, children hungry, commercial sex work one of few options open to many women); deep history (polygamy was practiced in tribal villages); recent history (men had to leave their families to find work during segregated colonial rule); tradition (young girls tend to couple with older men who, having longer sexual histories, are more likely to carry and transmit the disease).

Indeed, the risk is so disproportionate, the cultural barriers so great, that global health workers no longer rely on male condoms or abstinence to slow the pandemic.

Instead they focus on women, who carry the threat of the disease in their blood and the burden of caring for the sick on their backs. Half a world away, in resource-rich Seattle, work is being done to improve female condoms, diaphragms, virus-killing gels — anything to help women protect themselves during sex.

And while it grows too late for Ruth's generation, they look to the future, to little girls like Martha.

The race to save them is a race against the virus, against hormones, against politics, against custom, against the clock.

AIDS, left unchecked in the developing world, threatens to rival the Bubonic Plague, which swept out of Asia in the 1300s and, by the 1400s, had ravaged a third of the population in China and Europe. Virtually unknown two decades ago, AIDS now is the leading infectious cause of death worldwide. In Africa alone, it has taken more lives than all the soldiers killed in both world wars. It has crossed public-health borders, undermining economies and destabilizing nations.

"Clearly, in this more globalized world, having healthy societies, which are the cornerstone for stability and economic growth, is going to make the whole world better," says Dr. Helene Gayle, director of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation's HIV/AIDS and Tuberculosis program. "And, as a human, it's very difficult to think that just because of an accident of birth, somebody in Africa or Asia does not have access to a reasonable quality of health care. And someone who happened to be born in Seattle or Buffalo or Shreveport can have a reasonable expectation of a long, healthy life."

Numerically, malaria and tuberculosis together killed as many people as AIDS last year.

But AIDS has a crueler, more tragic quality. Other diseases spread in anonymous swaths through dirty water, tiny parasites, mosquitoes, droplets in the air. HIV infection is intimate. One-on-one. You get it from someone you know — likely from someone you love.

How do women live with love that leads to death? How do they negotiate safe sex in a society where they have little power? How do they protect their daughters?

Women in Ruth's world, no surprise, do what women everywhere do in hard times — they share what they know with each other. They take us into their confidence, their bedrooms, their kitchens and once, in a funeral lorry, into their laps. They talk women's talk in women's places — around the cooking fire, in a hair salon, in a circle of young brides learning from a feisty neighborhood grandmother how to please their husbands during sex and, perhaps, keep them faithful.

The surprise is the stigma AIDS still carries, even though every person has friends and relatives dead or dying, even though roadside billboards promote condoms more often than cellphones.

In Africa, the shame transcends worries of being shunned by neighbors or bosses. Some young women fear prospective in-laws will discover their HIV status and revoke the lobola, or bride price, traditionally paid at marriage. Others, with brothers and sisters already gone, fear another death would destroy their parents.

It's OK for the world to know, they say over and over. Just don't tell my mother.

|