TWO WEEKS before we met Ruth, her 16-year-old brother Esilon came home from school to find her sitting listlessly on a stump, her hair a mess.

Can you comb my hair? she asked.

|

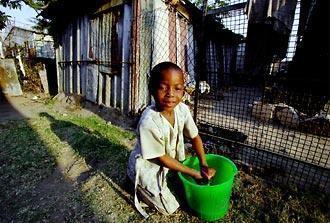

| BETTY UDESEN / THE SEATTLE TIMES |

| At 7, Anna Chiremba already knows how to sweep and mop, cook porridge and make tea — all skills necessary for a someday wife and mother. "She's doing a good one," her

mothers says proudly as her daughter washes socks in the family's yard. The Chirembas

live on the same street as Ruth’s family. |

|

|

|

In Shona culture, girls are taught to sweep, clean and cook; boys seldom share household chores. But Esilon has many older sisters, so he learned. And he was especially fond of Ruth. She had helped him compose poetry for his literature class. He had helped her rewrite notes from her HIV support group. Ways to protect from this deadly disease: Don't have many sexual partners. Only use sterilized razor blades. Get tested.

As he teased her hair with the comb that day, she told him the disease was back. "I was shocked," Esilon says.

Ruth faded quickly, wasted by bouts of diarrhea. She lost weight, even though her sisters tried to tempt her with sadza and the cucumbers she loved. The youngest, Ireen, fed her spoon by spoon.

When she had no strength to bathe, her sisters and mother boiled water over the fire, wrapped her skinny shoulders with towels and placed cloth down to buffer her from the cold concrete floor. They rubbed her skin with petroleum jelly to ease the sores.

"I wanted Ruth to know that I loved her and would touch her. It was up to God as to whether I would be infected or not."

— AMAI CATY, RUTH’S MOTHER |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Momma, since I'm so sick, I might die, she told Amai Caty. If I am to die, would you please look after my children very well?

Amai Caty shushed her fears. "...OK, my daughter. Let's see what's going to happen.' I was hoping she'd be all right."

Mercy canceled a trip to visit a brother in another township. She sat by Ruth's side to play gospel cassettes, pray and blow on the fire because Ruth always felt chilled.

Will you look after Martha and Tafadzwa when I am dead? Ruth asked Mercy. "Of course," Mercy answered. "But you're not going to die."

The day after we met, Ruth awoke hungry. She wanted chicken. Mercy rushed to the market to buy the fowl, a rare treat. While she was gone, Ruth's running stomach poured. Her two oldest sisters, Catherine and Regina, held her over the squat toilet while Amai Caty tried to wash the mess from her frail body.

Amai Caty was still washing her daughter when she realized Ruth was dead.

"Everywhere I touched her was cold and she had stopped breathing." Amai Caty thumps her right palm on her breast. "I felt pained. My heart had something like a lump."

· · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · ·

|

|

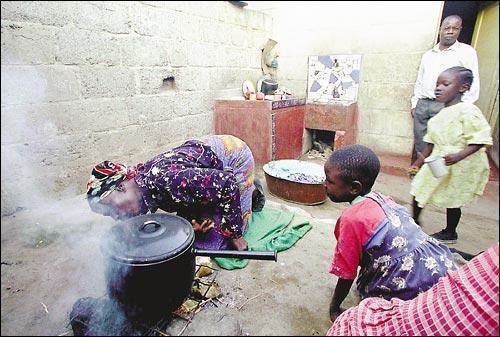

| BETTY UDESEN / THE SEATTLE TIMES |

| Ruth's mother, known as Amai Caty, shows her love through her hands. She raised 12

children with her husband, Robert, who supports the family as a sweeper and messenger.

Even as she cooks and cleans, Amai Caty finds time each day to heat and pour Robert's

bathwater. And when her middle daughter, Ruth, was dying of AIDS, Amai Caty did not

hesitate to touch her or clean her wasting body. |

|

|

AMAI CATY'S HANDS are strong as a tree and weathered as leather. The veins in her arms twist like roots into fingers that are sturdy as hardwood branches. Her thick thumbnails are ridged like bark.

From sunrise until the moon is high in the sky, for as many years as she has had a family, Amai Caty has used these hands to care for them.

After her husband leaves for his job as a city sweeper and messenger, she scrubs the bathroom, washes and dresses her grandchildren, breaks kindling, splits wood with an ax, lays and lights a gumwood fire, boils porridge, carries vegetables from the market, scrubs the blackened pots with dirt, wrings and pounds the clothes, irons with a charcoal iron, sweeps and sprinkles water on the dusty paths, wipes soot from the walls, and on and on until it is time to prepare tea and bathwater to be ready when her husband returns home. To warm the bath water, she kneels on the ground and breathes life into the fire. She lifts the heavy black pot using only small rags to protect her hands from the hot metal. She pours the water into a big plastic bucket then staggers with the bucket into the bathroom where Robert waits with an old-fashioned razor to bathe and shave.

Then Amai Caty starts supper.

Her daughters share the housework, but Amai Caty has always tended to her husband's tea and bath, even when she was pregnant, all 12 times. It's her way of showing she loves him.

And taking care of her children, Amai Caty says, that is a mother's love.

So when the end came for Ruth, Amai Caty showed her love with her hands. "I would wash everything that came out of Ruth," she says. "I never used any gloves. If I was to take plastic bags, like from the sugar and mealy-meal, Ruth would see me wearing the plastic on my hands and she would have stress. "Oh, my mother is seeing me like I am a toilet. My mother does not love me.' So I was touching everything with my hands. I wanted Ruth to know that I loved her and would touch her. It was up to God as to whether I would be infected or not."