BENNETT, B.C. - "CAUTION: BEARS ON THE BENNETT TRAIL."

The sign is clearly new and very official, highlighted with pink ribbons. It reiterates warnings from fellow hikers. And it gets my attention.

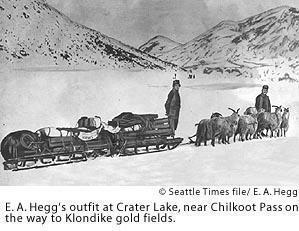

Four days I have been trodding northward from Dyea, Alaska, bound for Lake Bennett and, ultimately, the Klondike.

I am hiking alone now, setting my own pace, which is to say ponderous, savoring the open terrain, the big sky and the alpine-like life of the interior.

Back on the wet side, most of the gold-rush relics have long since been reclaimed by the dense, coastal rain forest. On this side, history is better exhibited in the sparse forests, better preserved by nature's refrigeration.

Here, on a rock next to Deep Lake, is a four-foot sled, its rusted iron rails wrapped elegantly around solid hickory runners. There's the iron skeleton of a 12-foot portable boat, shreds of century-old canvas still dangling from its frames.

But the prospect of confronting a bear is a tad sobering - especially alone.

I consult with Mont Hawthorne, my historical friend, and am quickly reminded that he, like most of the 1898 stampeders, crossed the mountains in the winter while the bears hibernated.

Now I trek the Lindeman to Bennett Trail, occasionally clapping or shouting my presence to the neighborhood bruin.

A mile up the trail, I hear a tromp-tromp from behind. This is no bear; it's the Czechs. Ten mountaineers from Prague, aged 25-60, who are not so much hiking the Chilkoot as marching it. Twenty-five miles back, I learned that the appropriate response is to smile and get out of the way.

The Czechs march past, nodding hello. Here's the bearded fellow with the guitar strapped to his pack, the 50ish fellow swinging his ski poles, and finally, Lida Prouza, about 5-foot-2 and 60-something, who carries a pack roughly her size and weight, and would carry mine, too, if I let her.

She stops and chats merrily, then resumes the march. I feel much better. If there are bears ahead, they must fend with Lida and company. My money is on the Czechs.

Bennett has no bears, just mosquitoes of bear-like proportions, a smattering of ghosts and piles of century-old trash.

A hundred years ago, the upper shores of Lake Bennett became what Klondike historian Pierre Berton calls "the greatest tent city in the world."

By the spring of '98, more than 30,000 people had poured over the mountain passes to the shores of this magnificent lake. Here they would pound together their boats and rafts, and wait for the ice to break up so they could launch the next, and last, stage of their exodus 600 miles through the vast mountain lakes and down the Yukon River to the City of Gold.

My friend, Mont, was one of them. As soon as he returned from his Chilkoot journey, he started looking for a place to build his boat.

"I figgered I'd have to move on down the lake," Mont recalls. "I kept walking and walking, but I wasn't getting below the tents pitched thick along the shore. . . . Blamed if the lake wasn't as crowded as the passes."

Eventually, he found his spot in a cove sheltered from the wind, with good timber that wouldn't have too many knots. And there he went to work, felling trees, sawing them into planks and assembling them into a sturdy, flat-bottomed scow capable of hauling his 1 1/2-ton Yukon outfit.

Unlike most of his fellow stampeders, Mont knew how to build a boat. So, on May 29, 1898, when the lake creaked and rumbled and the ice began to slither north, Mont was in the first wave of boats to follow it.

A city of 30,000 packed up its tents and moved on, leaving nothing but tree stumps, ghosts and garbage.

Today, Bennett sits silently at the top of the lake. There is no public road here, just a rustic church, a seldom-used railroad station and a campground for Chilkoot hikers like me and Mont. . . .

And anything the Klondikers didn't need to haul downriver.

There are piles of rusted tin cans and broken bottles extending from the lake far into the young forest. The forest itself is only now rebounding from the saws of '98. There are dozens of abandoned cookstoves, pots and pans and an enamel wringer-washer that looks like it might wash again.

To the modern environmentalist, Bennett is a morality lesson about waste and landfills, and fouling one's own nest.

To the historian or archaeologist, it is a treasure, a modern-day midden that offers important evidence about how people lived their lives a century ago.

To Mont and me, Bennett represents history of another kind. We have our mission. The ice is long gone, and we're on our way downstream to the gold fields.