CARMACKS, Yukon Territory - Even from a distance, the little red canoe looks to be in distress. Limping down Lake Laberge, the boat zigs and zags and re-zigs. Paddles flail and exclamation marks flutter overhead.

We change course and paddle over to say hello to two skinny youths with their backpacks stacked between them. We offer to help.

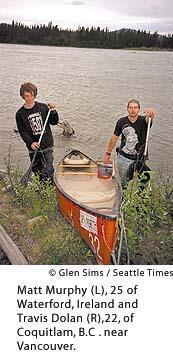

Travis Dolan, 22, is a sometime-student from suburban Vancouver, B.C. He had family problems, so he packed his bag and climbed aboard a northbound bus for the Yukon Country.

Matt Murphy, 25, is a student from Ireland traveling across Canada. He arrived in Toronto but decided it was too big, so he headed west for Vancouver and reached the same conclusion. He has read volumes of Jack London and Louis L'Amour and yearned to see the Klondike country. He bought a ticket on the same bus.

So Matt and Travis teamed up, strolled the streets of Whitehorse and heard the river beckoning. Between them, they scraped together $300 for a rental canoe.

And here they are, 50 miles downstream from anywhere, with little experience in the outdoors and none in canoes.

Old Mont, my historical pal, shakes his head sympathetically.

It was a typical scene a century ago, he says. The wilderness can make great friendships or destroy them.

Back in '98, he watched 10 longtime partners stand on the beach, splitting up their outfits. "They was putting little dried apples here, dried peaches there, a pinch of raisins over yonder. They was all watching each other close so they split up even.

"They'd had a bad falling-out, and none of them would go down to Dawson with each other. It looked terrible foolish, when all they had to do was float on down to Dawson together. But I could see it in their faces, they'd begun to hate each other."

Matt and Travis, however, seem good-tempered about their plight. We offered a quick canoe lesson: Pack your gear in the bottom to lower the center of gravity. The rear paddler steers and commands the canoe; the bow man paddles hard and switches sides only on command.

They listen and appreciate, and fellow kayaker Glen Sims and I paddle on downstream.

This wilderness is not empty. We can paddle for hours and never see a soul, then round a bend and encounter fellow travelers, all headed downriver.

Along the way, we encounter six government workers from B.C.'s Okanogan Country, on a two-week canoe trip.

We paddle past a middle-aged Japanese man traveling with his black dog at the bow of his canoe.

We drift for an hour or so with Frank James and Bob Compton, semi-retired friends from North Pole, Alaska. Compton paddles a collapsible kayak, his bulging belly occupying most of its oversized cockpit. James sits in a chair high atop his new inflatable, a cross between a kayak and a rubber raft. His fishing pole dangles over the stern; a heavy rifle is ready at his feet.

There is a gray-haired couple from Germany who wave from their campsite, then signal us to please paddle on to another one.

The Yukon River has become an increasingly popular destination for low-risk adventurers, amateur historians and curiosity seekers.

It's easy. Whitehorse has plenty of outfitters who, for the right price, will put you in a canoe or kayak, shove you off the beach and fetch the boat two weeks later in Dawson. It has become a staple of the local economy.

But, as Mont attests, it is not always as easy as it looks. There are no serious rapids below Whitehorse. But there is 33-mile-long Lake Laberge, where a stiff northerly wind can stop or swamp a canoe like a brick wall. There are campsites where the air is thick with bloodthirsty mosquitoes and black flies.

And the river itself is not as serene as it appears. It gurgles and swirls. Every year, it claims more lives.

And friendships.

Carmacks, where the river intersects with the highway, is our halfway point. We interrupt our journey for a day to hook into telephone lines and transmit these words back to the city.

For a few hours, life becomes complicated again, aggravated by telephones and fax machines, credit cards and restaurant bills. We yearn to be back on the river, where we will be safe again.

And I wonder about Matt and Travis and their grand, spontaneous adventure. They seem solid, self-assured. But I wonder, all the same.

We wander into the local tavern for a cold beer. And there they are, the Canadian and the Irishman, halfway through a pitcher of pale ale and shooting a round of pool.

We meet again. Their adventure goes well, they say. They dumped their boat once, but dried out and pressed on for Dawson.

And what are they learning? Travis seems to have forgotten his family matter. Matt is living his L'Amour novel.

"Maybe I'm proving something, maybe not," Matt says. "But I'm having a great time - except when Travis steers the boat."

"Me?! When you're in front, you're supposed to be doing those long strokes, but you do those short, quick ones that don't get us anywhere."

They laugh and hoist a beer.

The next morning, I hear the rest of the story. Matt and Travis closed the bar last night, then wandered down to the river with some locals.

One of their new friends is stone drunk and falls into the river. The current tugs him away from shore.

Travis plunges into the Yukon, grabs the fellow and pulls him back to shore, saving a life.

I don't worry anymore. The kid's a sourdough.