|

|

|

Part 1 / The Corporations

Copyright ©

1998 The Seattle Times Company Posted at 09:35 p.m. PDT; Sunday, September 27, 1998

Mining company has close ties with government in proposed land exchange

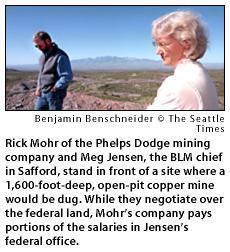

SAFFORD, Ariz. - The law says the federal government may not trade away the taxpayers' land unless the public interest is being served. So why, critics wonder, is the Bureau of Land Management on track to make two trades that will benefit the most powerful mining company in North America and permanently scar the topography on both sides of the Arizona-New Mexico border? A possible answer: The federal officials charged with making sure the deal is beneficial to the public and to the environment are being paid, in part, by the Phelps Dodge Corp. That revelation - discovered last year by a critic of federal land-trade policy and confirmed in documents obtained by The Seattle Times - has enraged opponents of the pending deal between Phelps Dodge and the BLM. Those opponents - environmentalists, area residents, union leaders and members of the Apache tribe - see the incestuous relationship as an explanation for why the government would be ready to give the mining company 20,600 acres for operating open-pit copper mines, in exchange for 4,600 acres of recreational land. "We have derisively referred to the BLM's Safford district office as the Phelps Dodge office of the BLM," said Peter Galvin, an environmentalist fighting the exchanges and a member of the Southwest Center for Biological Diversity in Tucson.

BLM defends the arrangement - which has been used elsewhere in its dealings with mining companies - as saving the taxpayers money. But it is also one of the most blatant examples of the close ties between the federal agencies in charge of land exchanges and the corporations with which they trade.

An investigation by The Seattle Times found that the land-trade business is an insiders' game, with timber and mining companies often controlling the game board. In this case, Phelps Dodge wants to expand two open-pit mines - including the largest in North America - and to dig a new one near where Apache warrior Geronimo was born. The mines to be expanded are at Morenci, Ariz., and Silver City, N.M.; the new one would be at Safford. The BLM land the company wants borders copper deposits it already owns. With it, Phelps Dodge could increase the size of the mines and have room for crucial operations such as waste dumping. The new and expanded mines could give the company access to copper worth $1 billion or more. The environmental issues are huge. An open-pit copper mine is a colossal man-made crater, as much as a half-mile deep and two miles across. It's evocative of the top of Mount St. Helens, only here the ripping of the land is done gradually, by explosives, bulldozers and trucks the size of two-story buildings. What comes out must go somewhere. A mine produces enormous piles of waste, which turn canyons and fields into plateaus and mountains. Sulfuric acid is dripped through some piles to extract the copper. Copper mines consume enormous quantities of water in an area where water is precious. There is also a threat of poisonous discharges to rivers near the mines. Residents near the New Mexico site worry Phelps Dodge will dig too close to a slender, 80-foot-tall rock spire known as Kneeling Nun, a treasured natural monument. Phelps Dodge disputes these concerns. The company insists it uses the safest and most modern mining methods. It takes considerable safeguards to protect water. It promises not to damage Kneeling Nun. Besides, the company insists, under mining laws, it could use the BLM land without owning it. The people in charge of sorting out all those issues are in the BLM's Safford office. Under a 4-year-old agreement, Phelps Dodge is paying part of the salaries of BLM employees reviewing environmental-impact statements for the Arizona trades; an EIS is required before the deals can be finalized. Although the agreement calls for the company to compensate two BLM employees, in practice the money is being spread over the salaries of 20 people. At the same time, the actual EIS reports are being done by private contractors paid for by Phelps Dodge and approved by BLM. Under a separate agreement in New Mexico, the company pays for consultants but not BLM time. Though the public saves up-front costs, critics say the arrangement gives the company an unfair advantage. "They are privatizing the public decision-making process," said Galvin. "It's insidious." Pat Shea, the BLM's director, insists the pay arrangement does not affect his employees' judgment. Phelps Dodge spokesman Richard Peterson said if the company didn't pay the bill, the government wouldn't have the resources to manage the exchange. Meg Jensen, the local BLM official who oversees land trades, said the office has been forced to trim staff from 82 to 50, and "if we weren't getting money from Phelps Dodge, we'd be letting people go or we wouldn't be filling positions." That's precisely the issue, said Janine Blaeloch, a Seattle environmentalist who specializes in assessing land trades and who discovered the agreement during a conversation with a BLM official in Phoenix. "When someone's job is dependent on completing a land exchange," Blaeloch said, you can bet the trade will be approved. And she's equally concerned about Phelps Dodge paying the private consultants doing the environmental reports. Regulations call for a 50-50 split of consultant costs between the parties in a land exchange. But companies know that offering to pay the entire bill gives them an upper hand and speeds the process, Blaeloch said. "They can grease the skids by taking on those costs themselves," she said. Yet, "if a private party is paying for and conducting wildlife surveys, there would have to be some doubt whether those surveys are going to be complete or fair." Phelps Dodge officials scoff at conflict-of-interest allegations. And they point out that they could lease the BLM land for mining without actually owning it. Under century-old mining laws, Phelps Dodge could simply lease the land for a nominal fee. Phelps Dodge is threatening to invoke that option if opponents create too many obstacles to the exchange, even listing that option as a first alternative in a recent environmental report. But critics, and even some BLM officials, insist that Phelps Dodge has a big incentive to trade: escaping federal mining regulations that apply to leased land but not to land a mining company owns. In a volatile industry where a penny-per-pound drop in the fluctuating world copper price can quickly cut annual income by $18 million, profits can hinge on something as mundane as the flexibility to move a waste pile. Moving piles cuts the distance traveled by ore-hauling trucks and speeds copper production. But these days, under pressure from Interior Secretary Bruce Babbitt, the government is threatening to toughen regulations that dictate such things as the location of waste piles. The company was concerned enough to warn stockholders about the threat to profits - and suddenly took an interest in land exchanges. On March 3, 1993 - just weeks after Babbitt took office - six Phelps Dodge representatives met in Safford with five BLM officials, proposing the Safford and Morenci trades, and were favorably received. The San Carlos Apaches and the Tucson-based Center for Biological Diversity have appealed the Morenci land swap to the Interior Department's Board of Land Appeals, and have promised to do the same when the Safford proposal reaches the appropriate stage. Others are poised to appeal the New Mexico trade. The appraisals that established the nearly 5-to-1 acreage ratio were paid for by Phelps Dodge, but BLM and company officials say they were fair and objective. Paul Robinson, a researcher for an opposition group, insists the appraisal was unfair. The scrubby BLM land is being valued on a comparison of what other desert lands near a mine would sell for, not on its profitability to Phelps Dodge as part of a mining operation. And although the trades are expected to create hundreds of new jobs, the United Steelworkers union, which represents mine workers, is opposed because of the anti-union history of Phelps Dodge. BLM in favor of the trades

BLM officials say they've listened to all the opposition, and they dismiss most of it. In interviews, employees in the Safford office were strongly in favor of the trades. One called approval a "no-brainer." Marvin James, the BLM's exchange coordinator in Las Cruces, N.M., acknowledged the agency's reliance on Phelps Dodge and the consultants it has hired. He said his office hasn't had an appraiser for two years, because of cutbacks, and has little experience handling trades. Likewise, when BLM natural-resources specialist Dwayne Sykes was asked about environmental concerns, he said: "Here again, Phelps Dodge is doing all of the study out there on the ground." The work actually is being done by a contractor paid by Phelps Dodge and cleared by the BLM, but the answer illustrates why opponents question these trades. And there's one more factor: Some feel the federal law under which the BLM operates requires the agency to help Phelps Dodge. "One of our primary purposes as an agency is to promote mine development, . . ." said Mike McQueen, project manager for the Arizona exchanges. "They haven't changed the law. We are really caught in a crossfire among different parties that promote different purposes."

|

|

|

[ seattletimes.com home ]

[ Classified Ads | NWsource.com | Contact Us | Search Archive ] |