Part 2 / The Speculators

Copyright ©

1998 The Seattle Times Company

Posted at 08:36 a.m. PDT; Monday, September 28, 1998

Private owners play game of backcountry speculation and win big profits, prime land from feds

Second in a series

DELTA, Colo. - In his line of work, Jim Dunn, a local land manager for the U.S. Forest Service, hears plenty of threats. So word that someone planned to build a luxury home smack in the middle of federally protected wilderness seemed like just more tall talk.

Until the helicopter came.

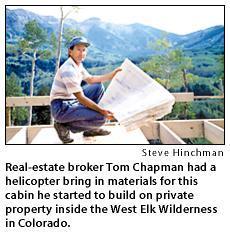

In the fall of 1992, Dunn heard that real-estate broker Tom Chapman and his partners had permits to build houses on 240 acres of private property inside the West Elk Wilderness, a world-renowned hunting paradise in western Colorado. Within days, the solitude of the aspen forest was shattered by the whup-whup-whup of a chopper ferrying in concrete and wood for a 3,400-square-foot, million-dollar log cabin.

Chapman's grand entrance - and his subsequent actions - seemed calculated to put the government on alert.

He built the sprawling cabin on a prominent ridgetop, visible from three directions for miles around. He scheduled noisy helicopter work during the first weekend of elk season, drawing complaints from touring sportsmen who had paid big money to hunt there. He told the Forest Service that he might mine for coal in the wilderness area.

With his activities and threats, he got the Forest Service's attention - and more.

Chapman agreed to burn down his cabin and trade his land to the government. In exchange, he received 105 acres of public land outside Telluride, the star-drenched ski town where Oprah Winfrey and Tom Cruise have spreads.

The government set the value of both the land it was getting and the land it was trading at $640,000. Within 18 months, Chapman sold his new Telluride parcel for $4.2 million.

One Colorado congressman called for the U.S. Attorney to investigate. Another demanded the Forest Service official who had approved the deal be fired. Conservation groups and conservative lawmakers fumed that the Forest Service had caved in to "greenmail."

All the critics agreed that Chapman - a bespectacled, small-town broker - had mastered a tenet of the federal land game: It's possible to make more money threatening to dig a mine, log a forest or build a subdivision in the wilderness than in actually doing those things.

"Chapman is one smart little boy. He showed up in Dodge and every one of our deputies got shot," said Congressman Scott McInnis, the Republican who represents western Colorado and is normally a property-rights advocate. "It looked like a methodical, laid-out strategy to create a little panic in the bureaucracy.

"He is to wilderness lands in the 1990s what the takeover sharks were to corporate America in the 1980s."

But while Chapman may be the Carl Icahn of the woods, he has plenty of comrades in eco-speculation. In some cases, the bounty is federal land; in others, it's cash:

-- Texas financier Charles Hurwitz threatened to cut down a stand of 2,000-year-old redwoods in Northern California, known as the Headwaters Forest. Officials rejected the idea of trading him an island off San Francisco. But with protesters dangling from trees, Congress and the state finalized a deal this month to buy him out for $495 million.

-- David Brask, a wealthy New Jersey investor, was arrested for bulldozing a road through grizzly-bear habitat to build a 360-acre subdivision outside Yellowstone National Park. Like Chapman, Brask has taken to the air, choppering in material for new roads and 30 cabins, which he says he'll remove if the government buys the land.

-- Mike Mitchell, a Seattle real-estate investor, turned a quick $250,000 profit by threatening to log a popular hiking area near Glacier Peak Wilderness in the Washington Cascades.

-- In the neighboring Alpine Lakes Wilderness, Cascade Development of Yakima threatened to exercise its mining claim on a 37-acre private parcel by detonating a 300,000-pound explosive unless the government bought the land - which it did.

-- In the 1980s, the Forest Service paid nearly $1 million for a private parcel in the Snowmass-Maroon Bells Wilderness near Aspen, Colo. But it didn't buy the mineral rights, which were snatched up by private investors who announced plans for a marble quarry. Now, Congress is considering paying another $4.2 million for the mining rights along aptly named Conundrum Creek.

The conundrum for land managers isn't simply how much money a speculator can make by forcing the government's hand. It's how such threats skew land-acquisition priorities at a time when there is enormous public pressure - but scarce money - to preserve wilderness.

Nearly half the $700 million appropriated last year by Congress for buying sensitive lands went to manage two crises: halting logging of the Headwaters' redwoods and stopping a proposed gold mine on the edge of Yellowstone National Park.

What Chapman and the others have shown is that the New West of ski resorts and million-dollar vacation retreats isn't all that different from the Old West of mining and timber camps: Smart speculators can still make a fortune off federally owned lands.

As the population of the West has tripled in the past 40 years, the remaining wilderness has become increasingly marketable. Technology can bring modern conveniences to the most remote locations, if someone's willing to pay for them.

Chapman and others who own what are known as "inholdings" - private land within the boundaries of federal wilderness areas, forests or parks - grumble that the feds rob their property of value by restricting access to it. But that's only half the story.

In fashionable areas such as Aspen or Sun Valley, Idaho, property that borders federal land is hot real estate because it comes with a guarantee of relative solitude.

Indeed, the appraisal of Chapman's West Elk property noted that its most striking sales feature was its location within a protected wilderness area.

In 1964, Congress created the first official "wilderness" - 9 million acres where no buildings, roads or anything mechanized, not even a chain saw, would be allowed. There are now 104 million acres set aside as wilderness. And the boundaries have expanded much faster than agencies' capacity for buying out private-property owners left inside.

The Forest Service estimates there are 460,000 acres in such inholdings within its wilderness areas. The law prohibits the government from condemning them; rather, the private owners are guaranteed "reasonable access," an ambiguous term that has provoked legal battles.

Even with money for land acquisition in short supply, the Forest Service has aggressively sought to buy up or trade for many of these parcels.

Inholdings "are all ticking time bombs," says N.J. Erickson, Forest Service land manager for the Pacific Northwest. "Anytime I can buy an inholding, I buy it."

The Forest Service has been particularly aggressive in Colorado. In turn, that has fueled a growing market for inholdings. Developers buy them up as trading chips for valuable federal parcels near ski areas. Others specialize in reselling old mining claims inside wilderness areas back to the government.

The price of even the most remote inholdings in Colorado has nearly doubled in the past few years.

Chapman has done his part encouraging the runup. He mails real-estate sales pitches to other inholders, noting how "very easy" it was to build a home by helicopter.

"Chapman being out there, contacting these owners and telling them that these are worth a lot more than anyone else believes, has really raised expectations," says Mark Pearson of the Wilderness Land Trust, a nonprofit Colorado group that buys up inholdings for preservation. "A lot of people suddenly think they're sitting on a gold mine."

While environmental groups fume, they sometimes aid the cause of speculators. Sue Gunn of the Wilderness Society says environmentalists have rarely made price - or value - an issue in preservation. For example, at Conundrum Creek, her group believes the $4.2 million pricetag is too high.

"We had to swallow real hard because a lot of us would have liked to called the owners' bluff," she said. "The locals just saw it as a grand opportunity to get these guys out."

Chapman belies his cowboy-country roots. He greets visitors at home in shorts, thongs and a golf shirt. Apart from his land deals, he's best known in his dusty railroad-and-ranching hometown of Delta as a terrific piano player.

The West Elk Wilderness is a hunting mecca, but Chapman does much of his stalking with professional camera gear. He quotes wilderness icon John Muir as avidly as any Sierra Club member.

And in a business where bluster is common, Chapman is known for action.

In 1984, he represented a rancher trying to sell his spread adjacent to the Black Canyon of the Gunnison River National Monument, a spectacular gorge that attracts 230,000 tourists a year. Dissatisfied with the National Park Service's offer, Chapman rented a bulldozer and began laying out roads for a housing subdivision on the canyon rim. After an appeals court ruled the Park Service's appraisal was too low, Congress paid $2.1 million for the ranch.

In the West Elk Wilderness, Chapman started out as a broker for another owner. The Forest Service, long interested in buying the 240-acre inholding, was offering about $1,000 an acre. Chapman insisted it was worth about $5,000 an acre.

"They said it was a national treasure," Chapman said, "so we shouldn't have been arguing it was worth only Appalachian prices."

He formed a development company to buy the property. He then set about raising its value - and the stakes. He positioned himself as both a champion of property rights and a defender of the federal wilderness system, warning politicians that unless the government struck a fair deal with him, his efforts would spark copycats and blemish Colorado's most pristine areas with trophy homes for the wealthy.

"As we continue with our West Elk building project, the resulting huge publicity we get is showing other inholders exactly what to do," Chapman wrote to Republican Sen. Hank Brown. "Unless we implement an aggressive exchange program immediately, our Colorado wilderness system will indeed fall into the hands of the rich, if not the famous."

Indeed, his tactics did push up the worth of the West Elk property.

An appraiser selected by the Forest Service upgraded Chapman's land to a high market value - in part, he said, because the controversy surrounding his helicopter construction methods had generated national attention. The appraiser said the controversy had made a "psychological contribution" toward proving there was a market for million-dollar houses in the wilds of Colorado.

"He convinced this office that he had some high-end buyers lined up. There is definitely an elite public with a big-enough pocketbook to buy 100 acres in the West Elk," said Dunn, the local Forest Service land manager. "Six houses there would have destroyed it as a wilderness."

Chapman concurs that the West Elk, if it were to remain pristine, was no place for a home.

"I was supporting the private owner's right to build one," Chapman said. "You create value for these properties by using them. The government's whole premise is that you won't. So if you're not using your property, you've kind of acquiesced to the system."

A deal for ski-town site

Not only tree-huggers were riled by Chapman's fly-in cabin. Other locals, while largely contemptuous of the government, didn't like anyone messing with their hunting grounds.

Eventually, Sen. Brown pressed the feds to deal with Chapman. So the Forest Service came up with a list of six properties near ski areas that might work in trade. Chapman picked the site near Telluride.

That simply shifted the protests from the West Elk to the 10,000-foot-elevation ski town 150 miles south.

What fuels Telluride is evident on Main Street, where T-shirt shops have been replaced by real-estate offices. In a county of 5,000 people, there are 120 licensed realtors.

On the mesas ringing Telluride, ostentatious stone-and-log vacation chalets duke it out with the majesty of the San Juan mountain range. Housing is so expensive that the city set up sites where restaurant and shop workers could live in their cars.

As in most ski towns, much of the best remaining buildable land is in Forest Service hands.

The 105 acres traded to Chapman is stunning: A stand of aspens sweeps gracefully into a meadow that is filled each summer with wildflowers. The porch of any future house will have a 270-degree alpine view dominated by Mount Wilson, the craggy peak featured on Coors Beer labels.

Only a few years before, the Forest Service had planned on expanding its holdings in the area, not disposing of them.

"He didn't just get forest. He got some of the most spectacular forest there is around here," grumbled Mike Farney, whose family owns a neighboring guest ranch and unsuccessfully appealed the exchange.

But what most upset the local residents was the value the Forest Service put on the property Chapman received. The appraiser assessed the 105-acre parcel at $640,000 - the value he had put on Chapman's 240 acres in West Elk.

About a mile away, Oprah Winfrey had spent $3 million for 85.4 acres three years earlier. San Juan County Assessor Jane Hickcox says no properties in the area had sold for less than $20,000 an acre since 1990 - and that is three times the $6,100 per acre the Forest Service put on Chapman's new land.

Chapman proved far more savvy than the Forest Service at gauging market value. Once he had the Telluride property in hand, he launched a national marketing campaign, complete with color brochures. His buyers, a prominent Hollywood producer and an East Coast retail executive, paid about $40,000 an acre.

Admittedly, pegging values in a hot market is tricky. Even an appraisal done by foes of the trade came in below Chapman's resale price. But it was twice as high as the Forest Service's appraisal.

"I just think there was so much public and political pressure to end this problem that the Forest Service was determined to make the numbers fit," charges Jon Mulford, head of the Wilderness Land Trust.

Paul Zimmerman, acquisitions manager for the Forest Service's Denver office, concedes that Mulford's views are widely shared, even though reviews by the Forest Service's Washington, D.C., headquarters and the U.S. Attorney found nothing improper with the appraisals or the trade.

"The appraisal said the two properties were of identical value, which made everyone think we were playing ball with Chapman and that something smelled," said Zimmerman. "The fact is, we made an environmentally and fiscally sound decision. But we got roasted for it."

No end in sight

The Forest Service may not be finished with Chapman. In the past two years, he has bought at least four mining claims in federal wilderness or proposed wilderness areas.

He paid top dollar, four or five times what the Forest Service believes those lands are worth. He told officials he planned to build a guest lodge on one parcel, tucked deep in an isolated, steep mountain slope. On another site, the Forest Service said Chapman planned on reopening an abandoned road to a silver mine before being told to cease.

Chapman has since resold those parcels to a partnership. He says he's no longer financially involved, but might later work as a consultant or broker on those lands.

Even if Chapman is out of the wilderness-investment business, there remains incentive for others to copy his playbook. Critics complain that despite recent efforts to buy up inholdings, land acquisition is so poorly funded by Congress and moves so slowly that the only way for many owners to strike a deal is to create a credible threat.

"As a practical matter, you often have to do something dramatic to get the Forest Service off their duff," said Mulford. "If an owner really wants to unload one of these properties, it doesn't take them long to figure out how the game is played."

|