Part 2 / The Speculators

Copyright ©

1998 The Seattle Times Company

Posted at 08:39 a.m. PDT; Monday, September 28, 1998

Millionaire, forest official want a swap; public goes 'ballistic'

ALTA, Wyo. - Millionaire Spencer Kirk wanted his own mountain hideaway where he and his family could commune comfortably with nature.

ALTA, Wyo. - Millionaire Spencer Kirk wanted his own mountain hideaway where he and his family could commune comfortably with nature.

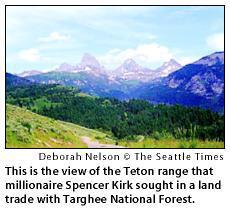

He had his eye on 580 wooded acres in the Teton range, with a front-row view of a stunning series of granite peaks.

Only one thing stood in his way: This was public land, part of the Targhee National Forest.

So he did what many a speculator has tried in the New West: He bought a private parcel of sensitive land on the U.S. Forest Service's most-wanted list and proposed a swap, then threatened to develop it when he didn't get what he wanted.

What makes his story different than most tales of speculator stickups is that the Forest Service handed him the gun.

Records show he bought the land as trade bait with the advice and support of the Targhee forest supervisor.

The land, known locally as Squirrel Meadows, is a 480-acre ranch located 13 miles inside the national forest.

It had been the object of similar speculation off and on for 20 years. Its value as leverage to speculators took a big jump when the Forest Service declared the surrounding area a grizzly-bear-recovery zone in the 1980s.

Forest Supervisor Jerry Reese pronounced the ranch his top priority soon after his appointment to Targhee in 1994: "It's a big meadow right square in the center of the most productive grizzly-bear-management area in the forest," he explained. "It's undeveloped now. We'd like it to remain that way."

But the land wasn't high enough on the regional office's priority list to get money to buy it. So Reese pursued land trades with a vigor that local residents, environmentalists and even some of his staff members found puzzling.

Everyone wanted Squirrel Meadows in public hands - but not at any cost. And, given the long history of empty threats about development, many questioned the urgency. The land, after all, is mostly wetlands, which can't legally be developed. The nearest utility lines are 9 miles away and the site is accessible by car only part of the year.

"You've got millions and millions of acres of wilderness around here, but this 480 acres has caught their fancy," said John McKellar, a Teton Valley realtor. "Each new forest supervisor keeps taking the challenge on of putting together an exchange. It's silly."

Within a year of Reese's arrival, a group of investors threatened to develop Squirrel Meadows if the Forest Service didn't swap it for federal land near Las Vegas.

Reese did what he could to make the deal happen. But interstate exchanges need congressional approval, and the Nevada delegation didn't think it was a great idea to give up hot commercial property in their state for ranch land in Wyoming.

By early 1996, the investors gave up. Ninety-five acres of Squirrel Meadows went to a private college, another 55 acres were set aside for a private cabin and 330 acres went up for sale.

That's when Kirk entered the picture. The young Salt Lake City entrepreneur had made his millions by marketing a modem for portable computers. He had sold his company, Megahertz, to U.S. Robotics in 1995, and retired soon afterward.

Kirk said he began looking for "a land legacy," a place he could build a family retreat that offered privacy with a view.

He heard about the availability of Squirrel Meadows. While it wasn't what he had in mind, he could buy it and offer to trade it to the Forest Service for a better location.

Before sinking money into it, his real-estate agent approached Reese to test the waters. Reese was receptive and provided a tour of Targhee for potential home sites, Kirk said. They settled on an area just outside the upscale hamlet of Alta, known as Teton Canyon - a scenic perch and rich wildlife habitat for elk, moose and great gray owls.

Reese recalls conveying a "willingness to consider" the trade, but nothing more. Anything more would have been inappropriate, he said, because he's supposed to remain neutral while exchange proposals undergo the required environmental evaluation and public comment.

However, records show Reese went further. In a letter of agreement sent to the agent right after their June 1996 meeting, he promised to "vigorously pursue the exchange."

"Squirrel Meadows is one of the most significant inholdings in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, and we are very interested in your proposal," he wrote.

On that representation, Kirk bought the 330 acres. And when he first unveiled his trade proposal to the community, he said he wanted to save Squirrel Meadows from developers: "The Kirks are sensitive to what Squirrel Meadows means ecologically and desire to no longer see it as an in-holding threatening the Forest with commercial development," said an early press release.

The public saw it differently. They saw it as a blatant power play to get the Teton Canyon property.

"The audacity of Spencer Kirk trying to buy 580 acres of mountaintop on the cheap," said Robert Crandall, a resident who lives below the canyon land. "It was presumptuous to think we'd roll over on that."

Public opposition swelled. There was a demonstration, a threat to sue, opposition from political leaders and environmental groups, a major letter-writing campaign. More than a hundred people wrote against the deal; barely any wrote in favor.

"People went ballistic," said Debra Patla of Citizens for Teton Valley, which opposed the exchange.

Kirk dropped his role as rescuer of Squirrel Meadows and threatened to build a subdivision on the sensitive land if the Forest Service didn't take it off his hands.

If he couldn't get his family retreat, he said, he wanted to recoup his investment and move on.

"I think he was somewhat amazed at the reaction," said Reese, who pushed the deal for nine months before caving to community pressure.

A new player: ski resort

It appeared Kirk would be stuck with Squirrel Meadows, in part thanks to Reese - until Booth Creek Inc. came to their rescue. The company operates the Grand Targhee Ski Resort on Forest Service property, along with numerous other ski centers throughout the country, including at Snoqualmie Pass in Washington state.

Booth Creek wanted to own the buildings and land at its resort. Reese said he'd be amenable to a trade - for Squirrel Meadows, of course. So Booth Creek paid for an option to buy the ranch from Kirk if and when the agency agrees to exchange it for the ski resort.

Reese's office is studying the proposal and awaiting the required appraisal and environmental analysis. But he's already publicly declared it a "win-win" proposition.

Many in the surrounding communities don't agree. In fact, this trade has enraged the public even more than the earlier proposal.

Only a few years earlier, citizen and environmental groups had won a court order halting an attempt to privatize the ski resort. In response to that order, the Forest Service spent $350,000 on a study that recommended against selling to private owners, in part because of concerns over the fate of the land if the business failed.

But Kirk is again turning up the heat. He has applied to extend underground telephone and electric wires through 9 miles of forestland to Squirrel Meadows. Some doubt he's serious about it; the cost could be as high as $300,000. But Kirk says the land will be developed if it's not traded.

"Should the exchange not be completed . . . I can assure everyone concerned we will expeditiously proceed with full development of the property . . . within the National Forest lying just four miles south of Yellowstone National Part (sic) and in close proximity to the Jedediah Smith Wilderness," he wrote to the Forest Service.

In an interview, Kirk called the letter a "cry of desperation" to take the land off his hands. "Development is the last thing I want to do," he insists.

Reese said he has little basis for rejecting Kirk's request for an easement, even though the area around Squirrel Meadows is protected bear habitat. He cited federal regulations that require the Forest Service to grant private-property owners "reasonable access" to their inholdings.

But those regulations specifically exempt utility easements. Reese later said he knew about the exemption but still felt he'd be hard-pressed to deny the application.

"It's a question of how far you go to block private development," he said.

|

ALTA, Wyo. - Millionaire Spencer Kirk wanted his own mountain hideaway where he and his family could commune comfortably with nature.

ALTA, Wyo. - Millionaire Spencer Kirk wanted his own mountain hideaway where he and his family could commune comfortably with nature.