Part 3 / The Environmentalists

Copyright ©

1998 The Seattle Times Company

Posted at 09:00 a.m. PDT; Tuesday, September 29, 1998

Environmental groups profit from land trades

Third in a series

SAN FRANCISCO - Harriet Burgess' nonprofit organization has tony offices in one of the nation's highest-rent neighborhoods, with an across-the-street view of the pyramidic Transamerica Building.

Burgess' nonprofit does almost no fund raising, yet it covers annual operating costs of $2 million.

Burgess' nonprofit pays her $118,000 a year.

Burgess' nonprofit sounds a lot like a business, and that's how she describes it. Yet, the American Land Conservancy (ALC) is officially classified by the Internal Revenue Service as a not-for-profit entity, exempt from paying taxes.

Burgess is unapologetic about what she calls a real-estate business with an environmental purpose: She acquires private land, then trades it to the federal government to preserve it for future generations. She calls it "the work of the Lord," but admits she can turn a heavenly profit in the doing.

"Somehow there is this concept that nonprofits should not make money, which is an interesting concept when we are trying to run a business," she says.

But others - including the investigative arm of the U.S. Forest Service - raise questions about how Burgess runs that business, using gold-card political connections to get exclusive access to available government land. In addition, investigators say, Burgess and the ALC have manipulated the appraisal process to gain bargain-basement deals at the taxpayers' expense.

The American Land Conservancy is, in the vernacular of land dealing, a "third-party facilitator," one of a small group of nonprofit and for-profit organizations that obtain private lands to then trade to the federal government.

Burgess buys or options private land the government wants, offers it in trade for land the government doesn't want, clears away such obstacles as liens and legal problems, and closes the deal.

Occasionally, her 8-year-old organization loses money. But by the looks of ALC's offices and its bottom line, that doesn't happen often. Burgess says that if she does her job well enough, she turns a 25 percent profit.

The company maintains its nonprofit status, Burgess says, by plowing all proceeds back into operational expenses and land deals.

The story of Burgess and ALC is the story of how third parties - and, in particular, environmental groups - can manipulate the business of federal land trading for their own benefit.

In 1993, shortly after Bill Clinton was sworn in as president, Burgess got a call from the nation's capital. On the line was Bruce Babbitt, just appointed to head the Interior Department.

The two had a rich history. They met when Babbitt was governor of Arizona and, together, had helped form the Grand Canyon Trust, which pushed to protect the Colorado River from dam projects. Babbitt and his wife river-rafted with Burgess through the canyon, and he helped Burgess launch ALC in 1990. With his wife, Babbitt served on the ALC board until his appointment as Interior secretary.

"He called to talk to me about whether an exchange could be put together in Nevada," Burgess recalled. "I said, `Yes, and I'd love to do it.' "

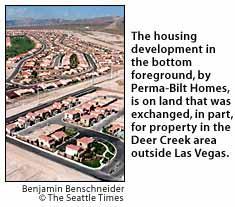

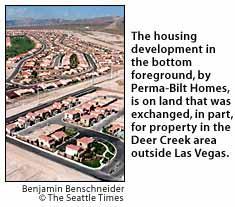

Babbitt explained that the Bureau of Land Management had $50 million worth of land outside North Las Vegas that was needed for expansion of the booming metropolitan area. By law, if the land was simply sold, the money would go to the budget of the Interior Department's Bureau of Reclamation and would not necessarily go to land acquisition.

But Babbitt didn't want money; he wanted land in the Southwest for conservation. Since the federal government rarely does outright real-estate purchases anymore, he knew that would mean a land trade.

In particular, Babbitt had his eye on a $20 million property near Reno that was slated for a ski area. But to obtain it for the $50 million North Las Vegas parcel, another $30 million worth of private land had to be found to balance the swap.

"I was supposed to put this together in 90 days," Burgess said, chuckling. The deal took nearly three years.

Before it was over, Burgess had obtained exclusive access to the best Nevada holdings of the biggest landholding agency in Babbitt's realm, the BLM. That meant she and her private clients got special leverage over land trades in a state where 77 percent of all acreage is owned by the federal government.

They also gained an edge in the hottest real-estate market in North America: Las Vegas, where a new house is built every three hours and where the BLM has been unloading 70,000 acres of residential land on the outskirts of the city.

In the process, the inspector general of the Forest Service says, Burgess got involved with federal bureaucrats in an illegal bargaining session in which she and a client persuaded them to accept suspicious private appraisals. That artificially raised the value of the land she was offering the government to an amount more than double what three senior federal appraisers said it was worth.

The taxpayers lost nearly $6 million in the deal and Burgess cleared $2 million, investigators say.

"This is a very, very serious set of circumstances," said Forest Service Chief Appraiser Paul Tittman.

In its report, filed last month, the Office of the Inspector General urged the government to get better control of third parties, which have monopolies over certain kinds of federal land exchanges in some areas of the country.

Federal bureaucrats are so outmatched by third-party operators that they gratefully turn the business over to them. Without third parties, some officials say, the government would be unable to pull off trades with private landowners.

The former head of Nevada's only national forest scoffs at the investigators' report, saying the inspector general is unfairly targeting Burgess while trying also to undermine such better-known third parties as the Nature Conservancy and the Trust for Public Land.

Burgess greets the criticism with a reminder that she is, after all, preserving land for eternity.

Burgess, 62, is a master at using her connections. But it takes more than a platinum Rolodex to be effective in the land-trade business. All who know her say Burgess has brains, experience and a blowtorch personality, and is indefatigable when the going gets rough.

The daughter of an Ohio minister, she first became involved in environmental causes as a volunteer in Washington, D.C., where her first husband was a federal housing official. When they split, she moved to California because it was "as far as I could go without going to sea."

There, she worked environmental issues for a congressmen and met her second husband, who represented oil companies. They live in the upscale hills above Oakland, and her friends say she doesn't need the money she makes at ALC. She said she hasn't given herself a raise in years: "I do this for love."

In 1978, she got her first exposure to the business of federal land trades as an employee of the Trust for Public Land. She served eventually as a congressional lobbyist and senior vice president in charge of TPL's western regional office.

Her signature effort was the creation of the Columbia River Gorge Scenic Area in Washington and Oregon in 1987. Burgess had bought the Gorge lands for TPL before Congress had even approved the scenic area. Deputy Agriculture Secretary George Dunlop blocked his agency's purchase of the lands, saying it wasn't a priority. Within days, Burgess had staffers from three senators' offices pressuring Dunlop.

He folded.

"It was sort of like a bulldozer," Burgess recalled. "One day I brought him a bunch of flowers because I thought he needed it."

Her break with TPL came on Earth Day in 1990. The departure was not amicable, and she and TPL signed an agreement not to talk about the circumstances.

"I left TPL because I like to do risky projects that might not work, and I liked to stay with a project," she said. "I'm always pushing the envelope. That's one of my sins."

Almost immediately, Burgess formed ALC - winning instant credibility through an impressive Board of Councilors that included politicians, environmental luminaries, writers - and Babbitt.

Since 1990, Burgess has engineered $210 million worth of land exchanges and acquisitions, making a profit on most of them. And no one stands in the way of her taking risks.

In search of property

Burgess is the first to admit that the call from Babbitt five years ago was a break. But she says she also had to make her own luck. To begin with, she worried that Babbitt's request to complete the Nevada land deal in 90 days was impossible, even for her.

It was, so she and the BLM signed a long-term agreement. The agency agreed to pool $48 million worth of federal land outside Las Vegas and to make it exclusively available to Burgess' organization, on credit. In exchange, ALC promised to find equal amounts of private land to trade.

Such arrangements are allowed by federal regulations. Without submitting any bids, an organization such as ALC can get a line of credit on prime residential land, with more than two years to make good on it.

Some question whether this kind of monopoly arrangement really serves the taxpayers.

"Normally when someone is in a position where they are going to do business with the government and reap a fair profit from it, they have to compete for that right," said Gerald Stoebig, former chief appraiser for the BLM in Nevada.

To come up with the land she needed, Burgess started with the $20 million property near Reno that Babbitt wanted. She then found a $10 million ranch at Pyramid Lake, Nev., plus some smaller parcels.

To complete the deal, she found $20 million worth of land in the California desert. But the Nevada congressional delegation didn't want it, preferring instead something nearer to nature-starved Las Vegas.

Finding trade bait near Las Vegas was tough, and Burgess was approaching her deadline. She had to locate enough land to compensate the government for $48 million worth of land, or pay the difference.

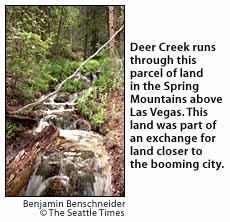

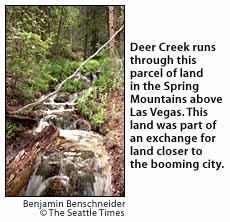

She pulled off a few more deals but was still about $8.5 million short when she found the missing piece: a property called Deer Creek, in the Spring Mountains above Las Vegas.

What appeared to be a dream come true, though, ultimately turned into what Burgess now calls "the Deer Creek nightmare."

Taking a risk on Deer Creek

Deer Creek is at 9,000 feet elevation, where the air is 30 degrees cooler in summer than in torrid Las Vegas. Aspens, ponderosa pines and bristlecone pines, some of the oldest trees on Earth, flourish there.

A dozen investors bought the 450-acre property for $2 million in 1992, intending to develop summer homes for the wealthy. Jan Bernard, the Las Vegas broker who led the group, sold 17 lots within nine months - sometimes, she says, by escorting buyers up to the property by compass and snowmobiles.

Burgess was friendly with Bernard, and in 1993 asked if she would trade Deer Creek for residential land in Las Vegas.

Bernard was interested, but there were problems. By selling divided lots, Bernard had created a checkerboard pattern of ownership. The rules for federal land exchanges say the government should be eliminating checkerboards in the national forest, not adding them.

But by late 1994, the Deer Creek property was the only land Burgess could find that was near Las Vegas and suitable for the trade Babbitt wanted. With the deadline nearing, ALC spent more than $3 million buying 80 acres of the checkerboard, and Burgess started trying to buy the other lots to eliminate the gaps.

Meanwhile, Bernard retained 380 acres of undivided acreage nearby, which would be part of the exchange.

Burgess was worried the government wouldn't accept the Deer Creek property because of the checkerboard ownership. And if she missed her deadline, she would lose not only millions of dollars, but the political support of environmentalists. She would be forced to sell the pristine land to homebuilders.

"If I sell the lots, I'll just be crucified by the people who are my supporters," she said.

That's when what Burgess refers to as the "appraisal war" began.

Appraisals sharply different

Burgess hired a Las Vegas appraiser, Keith Harper, to put a joint value on the Deer Creek tract she owned and the acreage still owned by Bernard's investors. Harper appraised it at $12.5 million - six times more than the amount the original investors had paid for the entire tract two years earlier.

The federal government, meanwhile, hired its own contract appraisers. The Forest Service - which got involved because it would ultimately be the recipient of the land - appraised it at $4.7 million. The BLM later compromised between the two and valued the land at $7.4 million.

At that price, Burgess would lose money. She was furious, and began working her connections.

"I was willing to do anything to save" the deal, she said. "I was so desperate, I was pushing the envelope."

She admits she telephoned her friend Babbitt at this point, but says he didn't call her back. She insists she never abused her political connections, but admits she was accused of invoking Babbitt's name, and others', during the appraisal battle.

Political meddling is a way of life with Nevada land exchanges, said Saundra Allen, a BLM deputy director in Nevada who went on sick leave last year due to an illness caused by the stress of the job.

"People throwing names out, saying I've got connections with this one, I've got connections with that one," Allen said. "After a while, I didn't pay any attention. I said, `I've got the American public to protect here.' "

In the spring of 1995, Burgess called Gordon Small, who was the Forest Service's director of lands, in Washington, D.C. He ordered his agency to let Burgess see the details of their appraisal and he sent Tittman, the agency's chief appraiser, to meet with Burgess.

Armed with those details, Burgess and Bernard met in Las Vegas with Nevada Democratic Sen. Richard Bryan, along with Forest Service and BLM managers.

Two federal employees who attended the July 1995 meeting say Bryan pounded his fist on the table and told BLM and Forest Service officials he didn't care what the government had to pay, he wanted them to make the trade work.

Bryan's chief of staff, Jean Neal, said her boss favored the trade because it would prevent further development at Deer Creek.

Burgess said Bryan called the meeting on his own and she personally doesn't remember him slamming his fist. She concedes, though, that the meeting was a key point.

Burgess was invited to another meeting with Forest Service and BLM officials and a member of Bryan's staff, this time in Reno. She was promised a review of the government's appraisal, one she thought would include interviews with Las Vegas-area developers. Instead, the agencies arranged a review by three BLM and Forest Service appraisers.

To Burgess' dismay, those appraisers arrived at a figure even lower than the original government appraisers.

"We are not making progress here," Burgess says she told them.

At that point, she made an end run, using her connections.

One of her main conduits was Jim Nelson, supervisor of the Humboldt-Toiyabe National Forest, the forest to which Deer Creek would be added. Nelson had been friends with Burgess since the early 1980s, working on other Nevada projects.

The inspector general found that Nelson's office had an "accommodating relationship" with Burgess. The American Land Conservancy got inside information not shared with other land traders, and whenever Burgess brought a deal to the Forest Service, it was automatically given a higher priority than others, investigators said.

Nelson and Burgess are open about their friendship. "I hold her in high regard and I won't apologize," Nelson said. When he was married in 1997, Burgess invited the newlyweds to San Francisco to go sailing.

But Nelson and Burgess said their friendship had nothing to do with the Deer Creek transaction or any others. Nelson said he was an enthusiastic supporter of the exchanges because they were good for the public.

The trade is completed

Suddenly, things began to move smoothly for Burgess in the Forest Service bureaucracy. Unbeknownst to BLM officials in Reno or even to the chief Forest Service appraiser in Washington, D.C., three Forest Service officials from Ogden, Utah, met with Burgess and Bernard in December 1995 to settle the deal.

The Forest Service team arrived at the meeting so ill-prepared that it gave Burgess nearly all she wanted, according to the inspector general.

The Forest Service officials set the value of Deer Creek at $10.5 million. They hired Gary Kent, a Las Vegas appraiser who'd been used earlier by Bernard, to confirm the value. The inspector general and the government appraisers said he used unconfirmed and faulty data.

The Forest Service's chief appraiser and legal advisers warned that the negotiations had been seriously flawed. Even so, three months after the bargaining session, the Forest Service signed an agreement with Burgess and Bernard.

When the trade closed, Burgess met her deadline, and had $2 million to spare. She had finally obtained enough private property to compensate the BLM for its $48 million worth of residential land near Las Vegas. The Deer Creek land was added to the National Forest.

The taxpayers, meanwhile, had lost nearly $6 million.

Two months after the deal closed, a whistle-blower complained to the inspector general. The source hasn't been identified, but Nelson suspects the government review appraisers. Two months after the deal closed, a whistle-blower complained to the inspector general. The source hasn't been identified, but Nelson suspects the government review appraisers.

"Since the appraisers weren't involved in the bargaining, they went crazy," said Nelson.

In December 1996, Nelson called Burgess with bad news: The Forest Service had removed his power to approve land exchanges.

Plus, he told her, she, he and the Deer Creek deal were the subject of an inspector general's investigation.

Further, Agriculture Deputy Secretary Jim Lyons, the man with overall responsibility for the Forest Service, had ordered a review of agency dealings with third-party facilitators, which is still under way. In May of this year, Lyons took another step and ordered a 30-day hold on all third-party exchanges unless approved by the chief of the Forest Service or his deputy.

Lyons and others say understaffed and undertrained government bureaucrats are routinely outmatched in land exchanges by third-party negotiators such as Burgess.

"These folks are strong and savvy and they come after these weak-kneed government managers who get beat," said Fred Page, a retired chief appraiser for the Bureau of Reclamation in Montana.

Ron Ashley, another retired Forest Service appraiser, said, "No one champions the cause of land exchanges except third-party land-exchange organizations. Who is going to beat on the lawmaker's door (for the taxpayer)? Nobody."

Lyons acknowledges the difficulties.

"We have to be certain that we're safeguarding the public interest," he said. `More and more it's difficult to ensure we have the expertise for doing that."

Sen. Bryan, who worked for this trade, is moving to require the federal government to auction rather than trade government land in Nevada. Most proceeds would go to buy land for conservation, with the rest going to education and water projects.

Pat Shea, appointed last year to head the BLM, says he is purposefully keeping a distance from Burgess.

"I wasn't going to be involved in this delicate area with someone pushing the envelope," he said.

Burgess, meanwhile, is mystified by those who question her methods and motives.

"It's an uncomfortable situation," she says, "when you feel you are doing all these virtuous things."

|

Two months after the deal closed, a whistle-blower complained to the inspector general. The source hasn't been identified, but Nelson suspects the government review appraisers.

Two months after the deal closed, a whistle-blower complained to the inspector general. The source hasn't been identified, but Nelson suspects the government review appraisers.