Federal appraisers in land swaps sometimes find their opinions spell trouble

Fourth in a series

PHOENIX - Value for value. That's the heart of any trade, be it kids swapping Beanie Babies, teams swapping baseball players or federal bureaucrats swapping land with private owners.

Except that in federal land deals, the value of all bartered property must be documented by professional appraisers. That's for the protection of the public and of the landowners, so the trades are fair for both sides and neither gets the upper hand.

At least in theory.

Reality, says government appraiser Robert Grijalva, is often very different.

In fact, he and others say, it's not uncommon for land values to be artificially inflated or deflated in order to make a deal happen. In such cases, they say, there is a clear loser - almost always the public.

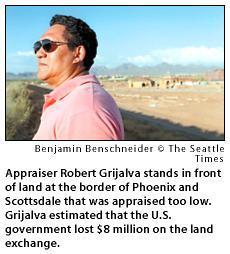

"Of course, in this case, I'm the fellow who lost," said Grijalva as he squinted through the desert sun to a north Phoenix commercial property the government traded away to a private developer three years ago. "I lost my job."

Pausing, he added: "And the taxpayer lost, too."

Opposition brought trouble

Four years ago, Grijalva was chief appraiser for the Interior Department's Bureau of Reclamation in Arizona. A veteran of more than two decades, his job was to assign appraisers, review their work and, most importantly, "to make sure the taxpayers don't get fleeced" in land deals.

It was an important job in a state where 42 percent of the land is federally owned. And Grijalva did it well.

College-educated in finance, he was known in government and private circles as a good, if sometimes obstinate, appraiser who played by the book.

"Being a chief appraiser is a tough job," he said. "You have to speak in words of one syllable and be blunt."

But Grijalva got in trouble - a lot of trouble - shortly after he tried to stop a deal in which the government was trading valuable commercial property in Phoenix to a developer for cactus-studded land outside Tucson.

Records obtained by The Seattle Times through the Freedom of Information Act tell the story: The developer and other private interests pressured upper-level federal officials, who pressured Grijalva's supervisors, who pressured Grijalva. When he refused to cave in, Grijalva says, he lost his job.

At one point, his boss wrote in a memo that he feared Grijalva's resistance might catch the attention of the Office of the Inspector General, which investigates government fraud. That office never got involved, though, and Grijalva's story was not made public until now.

The story provides a window into how easily and effectively the appraisal system can be manipulated in a federal land trade.

And although it's unusual for a government appraiser to be fired, appraisers involved in trades say the circumstances are all too familiar.

"If one review appraiser isn't playing ball, they take him off the case," said Gerald Stoebig, a former Bureau of Land Management (BLM) appraiser.

Grijalva didn't quarrel with the primary goal of the land exchange: to halt development next to Arizona's popular Saguaro National Park. He also understood why Bureau of Reclamation land was being traded: The National Park Service had no land of its own to offer in exchange for the private land bordering the park.

"I wasn't against the exchange," Grijalva said. "I was against the details."

"I wasn't against the exchange," Grijalva said. "I was against the details."

What troubled him most was evidence that taxpayers were being shorted by at least $8 million in the deal.

From the start, Grijalva was suspicious.

For one thing, the government was planning to use different appraisers to evaluate the two ends of the trade - one to evaluate the government land and the other the private land.

Experts say that's a dangerous practice. All appraisers have tendencies, with some conservative in pricing land and others liberal. There's a better chance for balance in a trade if the same person appraises both properties.

In this case, the appraiser who set the value of the developer's land next to the park was Al Benson, a certified private appraiser known by many of his peers as "High Val Al."

Benson says the nickname was unfairly given him by government officials involved in land-condemnation cases. But Greg Lee, a Tucson appraiser who recently filed a complaint against Benson with the state appraisal board, said of him: "It is embarrassing when your peers submit appraisal reports that don't seem to pass the test of sanity."

Benson was hired by the Park Service to appraise the land owned by the developer, Rocking K Development Co. The choice of "High Val Al" seemed curious to Grijalva and others: One of Benson's appraisals had already been thrown out by a federal court for being too high.

The Park Service has refused to release Benson's appraisal, but other government documents show Benson valued the 1,950-acre desert parcel at $22 million.

Grijalva assigned one of his employees, Norm Edwards, to look at the same parcel. His estimate of its value: $6.8 million, less than one-third of Benson's.

But that was only one side of the deal, and not even the most troubling. Even more disturbing to Grijalva was what happened to the appraisal of the government's property.

Grijalva had Edwards appraise the Bureau of Reclamation land, a 60-acre plot located in a bustling commercial area on the border between Phoenix and upscale Scottsdale. Six acres were actually owned by another Interior Department agency, but Reclamation was primarily responsible for it.

Edwards set the value at $10.6 million. That amount appeared reasonable; a November 1991 internal memo marked "don't distribute" had estimated the value at $10 million to $12 million. Another bureau memo, dated August 1991, cites a previous estimate of $16 million.

But Chris Monson, president of Rocking K, and others interested in buying the property from Monson, insisted it was worth less than $5 million.

Monson had promised not to profit from the trade, vowing to sell the land immediately for no more than the appraised value. But that meant only that the buyer would make the profit the public should have had, Grijalva said.

Monson and the potential buyer showed Grijalva's bosses comparable sales which they said supported the lower value. Grijalva discredited those sales, showing that five were distressed sales that shouldn't have been considered, one was from an irrelevant exchange and four were of residential properties miles away.

But Grijalva's bosses were swayed by the developer - and told Grijalva to back off.

Help from a congressman

Increasingly, Grijalva was seen as an obstacle to federal officials who - under pressure from a Tucson congressman who sits on the House Appropriations Committee - wanted the deal to go through smoothly.

It had been a long road. In the late 1980s, environmentalists and other civic activists had become alarmed when one of Arizona's wealthiest developers, Don Diamond, announced plans to develop a resort community on an old, 2,400-acre cattle ranch. The Rocking K Ranch, which he owned with other investors, bordered what was then known as the Saguaro National Monument and is now the national park.

The park covers rolling foothills on the east and west sides of Tucson, and is studded with tall, spectacular saguaro cactus and numerous other species.

The uproar led Diamond and his Rocking K partners, including Monson, to offer to deal with the government. Monson said they were as interested as the environmentalists in preserving the cactus land.

Congressman Jim Kolbe, a Republican supported by Diamond, stepped in to broker. He ushered through Congress a bill that expanded the monument, taking in nearly 2,000 acres of the land owned by Diamond. The bill, signed into law in June 1991, required the government to buy Diamond's land or to compensate him for it through a land exchange.

A follow-up bill in 1994 set the park boundaries and required more dealing for Diamond and Monson properties on the west side of Tucson. Congress didn't appropriate enough money to buy all the property outright, so a land trade was necessary. In fact, three separate trades resulted, the first of which was the trade Grijalva fought.

In January 1994, Grijalva's boss, Stanley Seigal, wrote a memo to one of his superiors, John Newman, suggesting that Grijalva be taken off the deal and that a new appraisal on the government land in Phoenix be done by a private appraiser.

In the memo, Seigal said he did not want another appraisal done by Grijalva's staff because it might become "the vehicle that sets me up for a(n) IG (Inspector General) investigation."

Two weeks later, Newman was on the telephone discussing Grijalva with a National Park Service official in Washington, D.C. During the conversation, Newman scrawled a comment in his journal that said Grijalva's appraisal "could undermine the exchange if made public."

Within the month, Grijalva was informed he was going to be fired for insubordination and other factors. Although one reason cited was that Grijalva had wasted government resources re-appraising the Rocking K land, Newman said the timing of the firing in the middle of this deal was coincidental.

Seigal, who is now chief real-estate officer for the Bureau of Reclamation nationwide, refused to discuss Grijalva's firing, citing privacy considerations.

New appraisal is lower

With Grijalva out of the way, the Park Service and the bureau hired a private appraiser to re-evaluate the federal land. That appraiser, Robert Francey, set the value at $5 million - less than half of what Grijalva's man had estimated, but right on the money for Rocking K.

Based on that appraisal and the one by Benson, the exchange deal was finalized. Rocking K would would give up only 430 acres of the 1,950 acres originally appraised - and, in return, would get the Phoenix commercial site and $1 million.

The deal was completed in March 1995. Grijalva estimates the public lost $8 million.

And today, the commercial site the government gave up - appraised at $5 million by Francey - is worth eight times as much, according to sales records on portions that have been recently marketed.

When the deal was concluded, Monson, the Rocking K president, sent a friendly letter of thanks to Bureau of Reclamation Chief Daniel Beard complimenting the agency's handling of the exchange.

Beard said in an interview that Monson is a friend, but insisted no strings were pulled.

"There were an awful lot of people that looked at it, in the solicitor's office and the agency," said Beard, now an Audubon Society official. "Obviously, they all thought it was in the public interest to do it."

Grijalva never went public with his battle, preferring to appeal his firing. He lost. Nearly four years later, he was hired as an appraiser by the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development.

In an interview with a reporter, he pointed to the corner of Scottsdale Boulevard and Bell Street as workmen hammered on a huge apartment complex under construction on the former government land.

"From this, I lost a 21-year career," he said. "My name was slandered."

As Grijalva spoke, guests walked out of two hotels that have sprung up on the property.

"It should have been auctioned or retained; it was a good piece of land," he said. "This whole issue of land exchanges is something that's disgraceful."

Monson, meanwhile, insists the exchange was perfectly fair.

"There are naysayers all the time and those naysayers traditionally don't do anything," he said. "They want to have private land for public purposes without any compensation."

Problems for appraisers

Other chief appraisers who have worked on federal land exchanges empathize with Grijalva. Ron Ashley, a retired chief appraiser for the U.S. Forest Service in Utah, and Stoebig, the former chief appraiser for the BLM in Nevada, both tangled with their bosses in cases that are the subject of a scathing report by the inspector general.

In the Nevada case, BLM officials, under political pressure, intervened to manipulate land appraisals in a manner strikingly similar to Grijalva's experience. When he wouldn't go along with his superiors, Stoebig was removed from a case and replaced by a private appraiser.

The problem, said Ashley and Stoebig, is that government appraisers report to officials who arrange the trades. Those realty officers, as they are called, are, in turn, rated by their superiors based on their success at closing deals, not on fairness to taxpayers.

An appraiser who challenges a deal "is seen as the guy who throws a bucket of cold water. He's not a team player," said Stoebig.

In Arizona, after Grijalva was fired, the "team players" kept on dealing with Diamond and his Rocking K partners.

Three years after the Phoenix-Saguaro trade, Diamond and his partners traded about 700 acres on the west side of Tucson to the Park Service for more than 4,300 acres of BLM land near the fast-growing Phoenix suburb of Peoria.

But unlike the earlier case, which was never widely publicized, this exchange hit the media and fomented an uproar. Opponents who knew nothing about Grijalva's earlier battles raised serious questions about the appraisals in the new deal.

Again, the man setting the value of the private land was "High Val Al" Benson. The BLM land was appraised by Con Englehorn of Phoenix.

Garry Davis, an appraiser hired by the opponents of the Peoria exchange, said he found many serious flaws in Englehorn's appraisal. He said the government land was valued at half its worth and traded away at a loss, perhaps $3 million or more.

Even the BLM realty team and Rocking K President Monson said the appraisal seemed low. Shela McFarlin, a project manager for BLM, said her team members looked at both Benson's and Englehorn's work and exclaimed, "What?"

Nevertheless, the BLM approved the deal.

An insiders' game

If there's a lesson to be learned from the Arizona exchanges, Grijalva says, it's that land trades are too much of an insiders' game.

The property isn't advertised. There is no bidding. Under those conditions, says Grijalva, "an unscrupulous appraiser can manipulate and do what he wants."

As the BLM's chief appraiser in the area, Grijalva was ultimately responsible for the valuation of the bureau land being traded. But he was unaware of the pending deal until a week after Monson and other Rocking K representatives had met with Park Service officials in San Francisco.

By the time Grijalva learned about the deal, Benson had been hired to appraise the Tucson land and Monson was already arguing with the Park Service about the value of the bureau land, records show.

The public didn't learn about the deal until two years later - and then, only in the tiny type of newspaper legal notices.

Even Harlan Hobbs, a retired realty officer who supervised the Rocking K exchange for the Park Service, wonders why the government doesn't abandon such transactions and move to dealing in cash.

"The reason they invented money," he says, "was that the barter system was slow and cumbersome."

"I wasn't against the exchange," Grijalva said. "I was against the details."

"I wasn't against the exchange," Grijalva said. "I was against the details."