Utah deal shows how congressional pressure can change rules to complete land trades

Two years ago, in a nearly empty chamber on the last day of their working year, U.S. senators approved the biggest public-lands measure in two decades.

The scene was tranquil and polite, although unusually rushed. The bill was nearly 700 pages and created parks, trails and historic centers in 41 states, but it had been hastily pasted together. When the House voted on it earlier, members could not even see the bill because it had not yet been printed.

On the Senate side, there wasn't even a vote. Most of the senators already had gone home for the year. Ten spoke glowingly of the measure, then they and a few others went on record that all 100 supported it.

Nobody mentioned that Congress had just granted an enormous plum to a Utah oil baron, trading him millions of dollars worth of the public's land so he could build a luxury ski resort. Even most members of Congress likely didn't know that buried inside the bill was one of the largest federal land trades of the century -- a swap of more than 350 square miles of forest with Weyerhaeuser that was never appraised to see if it was a good deal for taxpayers.

What came to pass in that law -- known as the Omnibus Parks and Public Lands Management Act of 1996 -- serves as a study of what can happen when politicians get deeply involved in dealing public land.

Even when proposed with the best of intentions, such as protecting natural resources, land trades executed by Congress often share troubling features. Environmental rules are suspended at the request of companies and developers. The usual ways citizens can monitor a deal -- reviewing records, appealing decisions or suing in court -- often are limited or canceled entirely.

Private companies increasingly are urging Congress to take the decisions out of the hands of federal land managers. They are succeeding. This year, more than 50 land trades are pending before Congress.

``The agencies are bogged down and the companies want certainty and they want speed,'' said Andy Wiessner, a consultant who shepherds trades for landowners. ``It's never easy to get a bill passed, but if something gets to be overwhelming out there, we've found it works out best to just take it to Congress.''

To find out what happens when Congress trades the public's land, The Seattle Times traced two of these deals back to their origins. One path starts high in Utah's Wasatch Mountains, at an obscure ski resort called Snowbasin. The other begins in the pine forests near Bill Clinton's boyhood home in Arkansas.

Fifth in a series

OGDEN, Utah - When U.S. Forest Service officials here decided they would trade a businessman 220 acres of public land so he could build a ski resort, almost nobody was happy.

Environmentalists appealed the 1990 decision because they thought it gave away too much taxpayer-owned land.

The businessman, R. Earl Holding, appealed because he said he wasn't getting enough land.

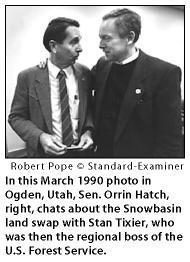

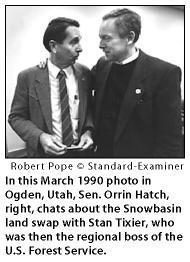

But nobody seemed more unhappy than U.S. Sen. Orrin Hatch, R-Utah. And Hatch was in a position to change things.

Hatch made it clear the Forest Service should grant Holding the land he wanted for the resort. Offering only 200 acres was a "dumb-assed, boneheaded decision," he said at a community meeting here. He asked if anyone else supported the ruling: "Well if you do hear of someone, I want to know. I'll kill them."

Then, Hatch put his arm around the man who was then the regional boss of the Forest Service, Stan Tixier, and said: "I've never asked Stan to help us yet that he hasn't done it. I hope that puts you on the spot, Stan."

Today, Earl Holding's plans for transforming Snowbasin from an unprofitable skiing backwater for locals into a posh, four-season resort town are moving forward. On a 9,000-foot-high peak in the Wasatch Mountains, special soft-treaded backhoes and hand-operated chain saws are carving out one of the world's steepest and most gut-churning race courses.

In 2002, the $21 million course will be at the center of the sporting world. Salt Lake City is hosting the Winter Olympics, and six marquee skiing events, including the men's and women's downhill, will be held at Snowbasin.

All of this was made possible when Hatch and the rest of Utah's congressional delegation finally delivered to Holding what he had always sought: 1,320 acres of public land at the base of the ski area.

That's six times as much land as the Forest Service originally had wanted to trade. The land to be traded away includes the type the agency is normally asked to acquire: wildlife habitat, watershed buffers and wetlands.

Details of the actual trade are still being negotiated. The public is expected to receive from Holding at least 4,000 acres of undeveloped forest and alpine scrubland scattered around northern Utah.

The legislation, which was inserted into the omnibus parks bill in 1996, decrees that the exchanged lands be valued at 1996 prices - unusual appraisal instructions that could give Holding prime resort land at a bargain.

Backers of the trade, including the Salt Lake City Olympic Organizing Committee, say it was crucial for getting Utah ready for the Games. Without the deal, they argue, Holding would never have spent money turning Snowbasin into a championship-caliber ski mountain.

But critics say the government is giving away far too much land at prices far too low, and that the primary beneficiary is not the Olympics but the politically connected Holding.

One of those critics is Tixier, the now-retired regional forester whom Hatch buttonholed at that public meeting eight years ago.

"It's a sweetheart deal," Tixier said recently. "The more land Earl Holding gets, the more money he'll make off this deal. I think a lot of people are just disgusted with the politics of the whole thing."

The Forest Service in 1990 increased its initial offer to Holding from 220 to 700 acres. But the project was plagued by environmental challenges and lay dormant for nearly five years.

Two events gave it a kick start: In 1994, Republicans won control of Congress; and, on June 16, 1995, Salt Lake City was selected as host city for the 2002 Winter Olympics.

Then, in the fall of 1995, U.S. Rep. Jim Hansen, a Republican who represents the Ogden Valley, introduced a bill that would force the Forest Service to complete the land trade with an even bigger ante: 1,320 acres, nearly what Holding had first sought years before.

As the newly installed chairman of the House subcommittee overseeing the Forest Service, Hansen was in a position to run with the idea. So was Hatch, now that Republicans controlled the Senate. And Holding had been a political friend and generous contributor to both.

The sales pitch used by Hatch and Hansen was simple: Without congressional action, the ski runs could never be readied in time for the Olympics. In a speech on the floor of the House, Hansen called the Snowbasin deal "a very minor land exchange" to create a venue for a ski race that will be watched by "3 billion people around the globe."

But Hansen made no mention of what Holding planned to do with the land and the 8,000 acres he owns surrounding it after the glow of the Olympic torch had dimmed. Holding's Sun Valley Corp. plans nearly 800 homes and condos, 1,000 hotel rooms, shops and a golf course - all within a 90-minute drive of the Salt Lake City airport.

The future of Snowbasin and other winter resorts has more to do with selling real estate than lift tickets. Skiing as an industry is stagnant: The number of skiers in the United States today is virtually the same as it was 20 years ago.

Promoting skiing has always been part of the Forest Service mission. But promoting real-estate development isn't - and records show that the officials negotiating with Holding worried about that.

"The justification for the project changed over time. Now it's the Olympics," said Ron Younger, a former federal employee and an environmental activist who grew up in nearby Ogden Canyon. "This is a giant real-estate development, masquerading as a ski project."

"The justification for the project changed over time. Now it's the Olympics," said Ron Younger, a former federal employee and an environmental activist who grew up in nearby Ogden Canyon. "This is a giant real-estate development, masquerading as a ski project."

The staff director of Hansen's committee, Allen Freemyer, professed little knowledge about Holding's long-term plans. The congressman's focus, says Freemyer, was the Olympics.

"If Earl Holding makes money off the land, then that's sort of capitalism at its best. I don't know why this is such a big deal. We're not going to bat for Earl Holding."

Jack Ward Thomas, chief of the Forest Service at the time, says he and his deputy, Gray Reynolds, advised Hansen that Congress had to act or else the deal could never be completed in time. They also suggested giving Holding more land than the agency had offered because part of the property is prone to slides and can't be developed.

Reynolds has himself become part of the ongoing controversy that surrounds the trade. Six months after Congress approved it, Reynolds resigned from the Forest Service. Almost immediately, he went to work as Snowbasin's general manager.

"There was no conflict here," Reynolds says. "While I was working on this, taking a job with the Sun Valley Corp. was the furthest thing from my mind. They didn't approach me until after my resignation."

How Holding turned a job as a manager at a struggling motel and gas complex in Wyoming into an oil and real-estate empire is the stuff of Western legend.

In the 1950s, he bought out the owner of the complex - dubbed "Little America" - installed dozens of new gas pumps and leveraged that success into a chain of gas stations and motels. In 1974, he added the Sun Valley ski resort to his holdings, restoring its aging glamour with a $100 million face-lift. A few years later, he bought Sinclair Oil - refineries, pipelines and hundreds of gas stations - from Atlantic Richfield.

Today, Holding reportedly owns more than 40 blocks of property in his native Salt Lake City. His net worth is $780 million, according to Forbes magazine.

He is renowned for avoiding the public eye. His corporate headquarters is in an unmarked building. When it came to the Olympics, though, Holding made a rare foray into the limelight. He joined the Olympic Organizing Committee board and donated $100,000 to the Games.

Last year, Holding gave his first interview in nearly two decades to a Salt Lake City newspaper. He said upgrading Snowbasin and other Olympics improvements were "labors of love at the moment" that wouldn't make him much money.

The company plans to invest $73 million outfitting the ski area with new lifts, restaurants and lodging before the Games, said Chris Peterson, Holding's son-in-law and a vice president of the family businesses.

But as a down payment on a future resort, the Olympics likely will make good business sense for Holding - especially with some additional help from the taxpayers. This year, Utah's congressional delegation inserted $15 million in the federal budget for a new access road into Snowbasin, a road Holding once said he would pay for himself. The Olympics will pay him $14 million to stage the six ski events at Snowbasin, including $4 million worth of snow-making equipment he will inherit when the Games end.

The land-exchange bill waived further federal environmental reviews of the trade and exempted it from legal appeals and lawsuits by environmentalists.

But Holding's biggest benefit figures to be the congressional mandate that the land in the exchange be appraised at 1996 prices.

In the past few years, real-estate prices in the area have been skyrocketing. Real-estate agents estimate prices in Ogden Canyon, near Snowbasin, have nearly doubled since Salt Lake City corralled the Olympics. Because the appraisal will be backdated, little of this run-up in value will be reflected in the trade.

Backers of the deal defend those special rules.

"The Olympics have sent real-estate values through the roof," said Freemyer, Hansen's aide. "It seemed unfair that because the Olympics were going to be staged at Earl Holding's ski area, the price he had to pay for that land would be all jacked up."

Others, though, are wondering why the taxpayers shouldn't reap benefits from the hot market just like any private company would.

"I think the integrity of the agency is on the line with this appraisal," said George Olsen, who retired in 1994 after overseeing much of the Forest Service's Snowbasin work. "For the public not to receive the full value of their investment out there is preposterous."

"The justification for the project changed over time. Now it's the Olympics," said Ron Younger, a former federal employee and an environmental activist who grew up in nearby Ogden Canyon. "This is a giant real-estate development, masquerading as a ski project."

"The justification for the project changed over time. Now it's the Olympics," said Ron Younger, a former federal employee and an environmental activist who grew up in nearby Ogden Canyon. "This is a giant real-estate development, masquerading as a ski project."